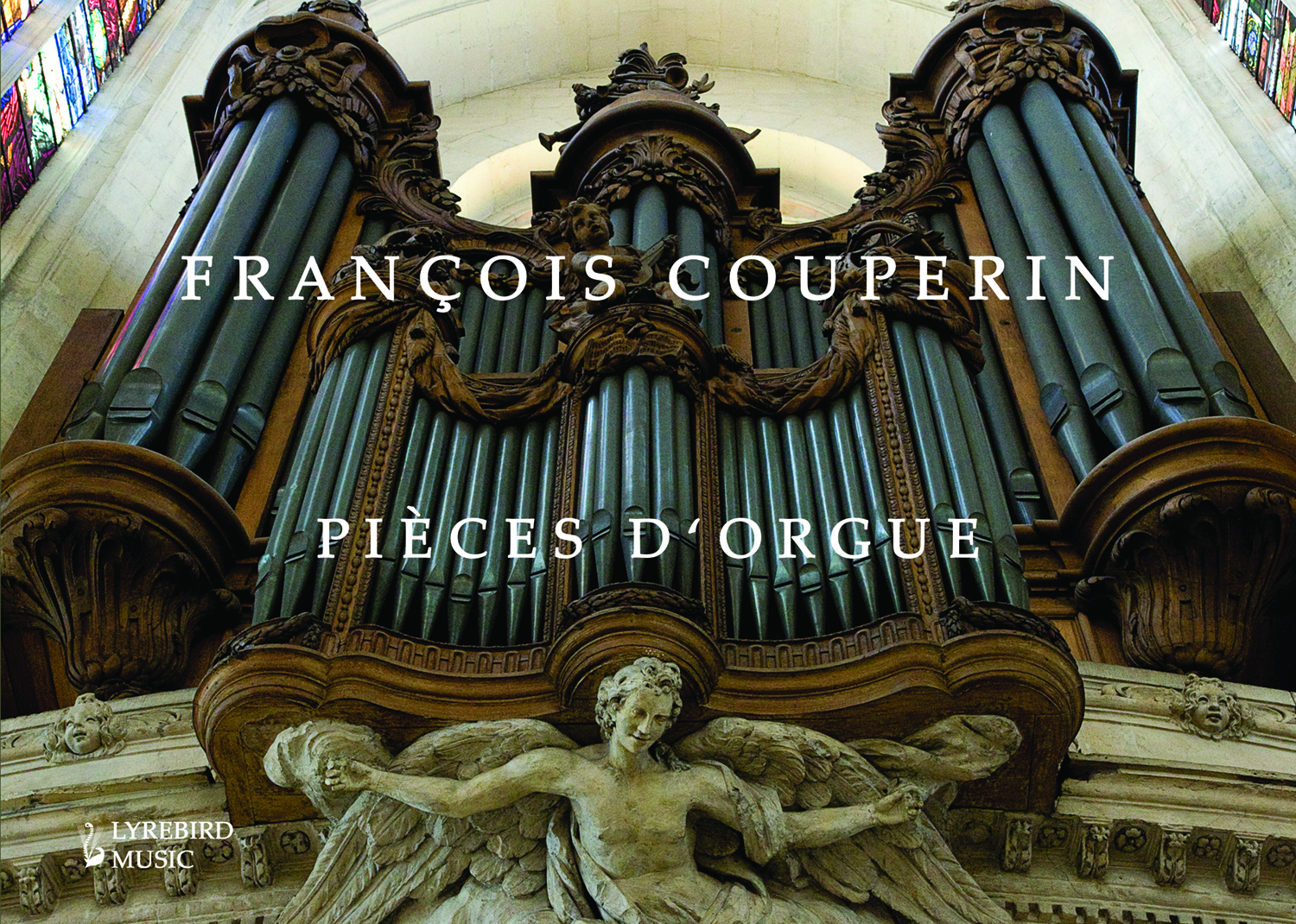

LBMP–001: François Couperin – Pièces d’orgue

From €37.82

ISMN 979-0-706670-00-3 (Hardback) | 979-0-706670-21-8 (Wire) 161 pages Edited by Jon Baxendale

- Two organ masses with appropriate plainsong settings

- Detailed notes on background, performance and registration in English and French

- Full commentary

- Critically acclaimed in peer-reviewed journals

- Three available formats

- Colour hardback cover with a matt finish (choice on checkout)

- Wire-bound with soft colour cover (choice on checkout)

- Tablet (PDF – one download available for 5 days)

Prices vary according to your needs. Please first choose the format you require.

Please note that if you are an EU customer, the prices include the VAT for your area. This is collected for orders under €150. EU customers whose orders exceed €150 will see the VAT until checkout, at which point taxes will be removed.

François Couperin’s only volume of organ music, Pièces d’ orgue, was not printed but published instead in manuscript format when the composer was just 21 years old. Nevertheless, the music marks one of the highpoints of French Classical organ literature. First published by Cantando Musikkforlag in 2018, this is the only commercially available critical edition. Editor Jon Baxendale revisits the five known sources to discover which is most accurate and provides detailed notes on the instruments of the day, ornamentation, notes inégales and registration.

For those wishing to perform Couperin’s music within a liturgical context, this handsome volume contains settings of Missa Cunctipotens genitor Deus for Messe des paroisses, along with propers for feast days with instructions on the order of service by Guillaume Gabriel Nivers. For Messe pour les convents, an appropriate plainsong setting by Paul D’Amance has been chosen.

This new critical edition, complete with an erudite and extensive preface, given in both English and French, is welcome … The standard of editorial work throughout is exemplary, including extensive critical notes … [and] notes on performance style and ornamentation are excellent.

John Kitchen

– Early Music Performer

We now have a newly-authoritative edition … underpinned by editorial knowledge, skill and sheer love … I honestly think that this is the publication that those who play the French Baroque organ repertoire have been needing for decades.

David Hansell

– Early Music Review

Baxendale’s fine edition offers a great deal of relevant information, with a pertinent bibliography, all of which will prove extremely helpful to both performers and scholars.

David Ponsford

– Journal of The Royal College of Organists

EARLY MUSIC PERFORMER

John Kitchen

This elegant new edition of Couperin’s Pieces d’Orgue, published in 2018 to celebrate the 350th anniversary of his birth, is the first to include the relevant plainchant which is an integral part of the alternating mass. This delivers the mass-text in sections, divided between a plainchant choir and the organ, the latter replacing half of the text. Every movement of the mass ordinary apart from the Credo was performed liturgically in this way; some organ movements are based on the relevant chant. By Couperin’s day the practice was well-established, and he would have been familiar with it from his teens. (He was already playing regularly in St. Gervais after his father’s death in 1679.) Many organists improvised the organ versets, but there was also a demand for published movements for alternatim use; along with those of Nicolas de Grigny, Couperin’s are considered the finest examples from an extensive repertoire. These versets are beautiful and graceful music, but they have much more impact when heard in conjunction with the chant. The inclusion of chant in Baxendale’s edition means that it supersedes all of its predecessors.

Couperin composed his two masses, the Messe pour les Paroisses and the Messe pour les Convents (or ‘Convents’) in 1690 at the age of only 21. When Alexandre Guilmant produced his otherwise reliable edition in 1903 the composer was believed to have been the elder Francois Couperin (c.1631—c.1710), Francois le grand’s uncle. During the 1920s, further research confirmed the masses to be the earliest known works of the younger Francois — remarkably mature and polished compositions for someone of his years. (Regrettably, he wrote no further organ music for the rest of his life.) By 1932 further source material had come to light, and in that year Editions de l’Oiseau-Lyre published, as their very first volume, a fine new edition by Paul Brunold which was several times reprinted. In 1982 l’Oiseau-Lyre presented a revision of Brunold, the work of Kenneth Gilbert and Davitt Moroney. This has an informative preface, in which they discuss (among much else) the merits and limitations of previous modern editions, including one dating from the 1970s by Norbert Dufourcq; of this they are critical, pointing out its unreliability. Since 1982, Gilbert/ Moroney has been the preferred modern text of most organists. (A Fuzeau facsimile has been available since 1986, and the music is now available online, both in facsimile and in various editions.) As Baxendale points out, the Gilbert/Moroney edition is now nearly 40 years old, and so his new critical edition, complete with an erudite and extensive preface, given in both English and French, is welcome.

Couperin composed his two masses, the Messe pour les Paroisses and the Messe pour les Convents (or ‘Convents’) in 1690 at the age of only 21. When Alexandre Guilmant produced his otherwise reliable edition in 1903 the composer was believed to have been the elder Francois Couperin (c.1631—c.1710), Francois le grand’s uncle. During the 1920s, further research confirmed the masses to be the earliest known works of the younger Francois — remarkably mature and polished compositions for someone of his years. (Regrettably, he wrote no further organ music for the rest of his life.) By 1932 further source material had come to light, and in that year Editions de l’Oiseau-Lyre published, as their very first volume, a fine new edition by Paul Brunold which was several times reprinted. In 1982 l’Oiseau-Lyre presented a revision of Brunold, the work of Kenneth Gilbert and Davitt Moroney. This has an informative preface, in which they discuss (among much else) the merits and limitations of previous modern editions, including one dating from the 1970s by Norbert Dufourcq; of this they are critical, pointing out its unreliability. Since 1982, Gilbert/ Moroney has been the preferred modern text of most organists. (A Fuzeau facsimile has been available since 1986, and the music is now available online, both in facsimile and in various editions.) As Baxendale points out, the Gilbert/Moroney edition is now nearly 40 years old, and so his new critical edition, complete with an erudite and extensive preface, given in both English and French, is welcome.

Couperin published the masses not in engraved editions, but in authorised manuscript copies; only the title-page is engraved. Baxendale thoroughly explores the complicated history of the source material in a preface modestly headed ‘A few background notes’. The source known as `Carpentras’ is the only known authorised copy, dating from 1690; while not in Couperin’s own hand, and the work of more than one copyist, it is the most authoritative. The other main source is known as ‘Versailles’, in which both masses are in the same hand; the copyist was responsible for the Messe pour les Convents in Carpentras. Although a major source, Baxendale explains why in his view Versailles does not have the authority attributed to it by Gilbert and Moroney in 1982. Other later copies are also considered, but they add little, save for minor variants, to the two principal sources. Like the original Carpentras volume, Baxendale’s edition presents the two masses in oblong format, on good quality paper and in beautifully clear print. Clefs are modernised, and important variants given in small type above or below the stave; original beaming of quavers is retained. The standard of editorial work throughout is exemplary, including extensive critical notes.

The initial organ movements of the Paroisses Kyrie, Sanctus and Agnus place the plainchant cantus firmus in the pedal, but sounding en taille on the pedal 8′ trompette, in the tenor; the sources notate it thus on two staves. Baxendale offers each of these movements both in this original layout, and also on the now customary three staves with the pedal at the bottom. I am not sure this was really necessary, but perhaps some will find it easier to read presented in this way. Couperin notates on three staves only in the tierce en taille and cromorne en taille movements, as well as in trio movements and sections.It is well known that French organ composers of this period (and indeed many up until our own time) almost always had specific registrations in mind; particular sounds are indispensable to an effective performance of the music (unlike, say, a Bach fugue which retains its integrity with whatever registration is chosen). Couperin follows this tradition, and in some movements gives remarkably detailed instruction, perhaps most notably in the fourth movement of the Paroisses Gloria: ‘Dialogues sur les Trompettes, Clairon et Tierces du G.C. Et le bourdon avec le larigot du positif. (The plurals here are probably wrong; more than one trumpet or tierce on the grand orgue was most unusual in Couperin’s day, and he certainly did not have these resources at St. Gervais.) Baxendale collates various contemporary registration and interpretative instructions — from Lebègue (1676), Raison (1688), Boyvin (1690), Corrette (1703) and others — and presents these in a useful table in the preface. Each Couperin movement is listed in order, with comments appropriate to each, and Baxendale adds a few glosses of his own. Although much of this information was published by Fenner Douglass in his monumental The Language of the Classical French Organ (original edition 1969) it is helpful to have it readily to hand in this new edition. Baxendale notes that organists today may be surprised by the prescribed use of the tremblant fort; five sources indicate its use in the big Grands jeux movements, that is, with the powerful reeds and comets. When heard on an eighteenth-century French organ, the effect is rather alarming to us; but apparently it was customary then. It is interesting how tastes change.Baxendale’s notes on performance style and ornamentation are excellent. Again he lavishly quotes contemporary sources, but interprets what they say — which is not always unambiguous — most perceptively. His discussion of the port de voix, where he quotes Bacilly, Saint-Lambert and Gigault, is especially absorbing. Finally, there is helpful advice about performing the plainchant included in the volume. The Messe pour les Paroisses is based on the well-known Cunctipotens genitor Deus chant, and Baxendale uses the version from the Graduale Romanum (Paris, 1697) which varies considerably from the familiar but anachronistic Liber Usualis version. Because it was intended for religious houses which used a variety of plainsong masses, the Messe pour les Convents is not based on chant, but freely written. In the edition Baxendale chooses the Missa de Ste Cecile, tone VI, from a Parisian source of 1687. Appendices give complete plainsong propers, again from a late seventeenth-century source, for those who wish to perform the whole mass liturgically. Baxendale notes that the chant was sometimes inflected with accidentals, ornamented, and sung in a measured style. A few modern performances have attempted this, such as one recorded in 2002 on the Triton label with Marie-Claire Alain and the vocal group Sagittarius. The musical text is accurate, although there is a missing accidental on p. 33 (bar 43) which is easily spotted, and a misplaced dot on p. 70 (bar 11) which initially causes confusion; p. 73 of the edition gives a facsimile of the page from Carpentras showing the correct rhythmic notation. There are also a few misprints in the written text: `Solonelle’ (p. 1) should have been noticed. (In Carpentras this word is spelled `Solemnelle’.) These are minor quibbles, however. It is very much to be hoped that this new edition will encourage many more performances of Couperin’s wonderful music, played in conjunction with the chant.

EARLY MUSIC REVIEW

David Hansell

It has always frustrated me that past generations of editors have thought it just fine to publish music in non-specialist, mass-distribution editions in a form that is not fully suitable for performance. I am thinking in particular of Renaissance music that lacks any indication that a plainchant incipit or insertion is needed and liturgical organ music that gives no hint of the chant that should surround it.

Well, at long last this latter issue has been addressed, at least for Couperin, by this handsome new edition of his two organ masses which may prove to be the most enduring memorial to have been stimulated by the composer’s 350th anniversary year – it has already been used for three recordings. An editorial re-consideration of the masses was long overdue. Their sources are complicated by the fact that the music, though ‘published’ by the composer, was never actually engraved and printed: what you bought was a printed title page but a manuscript copy of the notes themselves. In a spectacular piece of diligent research Jon Baxendale has carefully explored the whole musico-social-historical-commercial context of the surviving copies and their relationship to others that must once have existed and proposed a new and convincing stemma on which to base his work.

Indeed, what this publication contains in addition to the music is at least as important as it is. The lengthy introduction explores Couperin’s early life as an organist and the sources of the music; offers advice on performance style and ornamentation; and explains that this music is in the alternatim tradition, in which organ music replaces portions of the sung liturgical texts. Not only are the necessary chants and texts to complete the mass ordinary provided but there is also a set of propers. Needless to say, all the chant is from appropriate French sources. In addition, there is an explanation of the organs on which the repertoire was originally played, discussion of exactly which stops were used for what, and comments from other contemporary organists/composers – since we have none from Couperin himself – on the general character of each movement style. All these are evaluated and explained further, where this is needed, by the editor. The volume ends with a substantial critical commentary and a valuable bibliography.

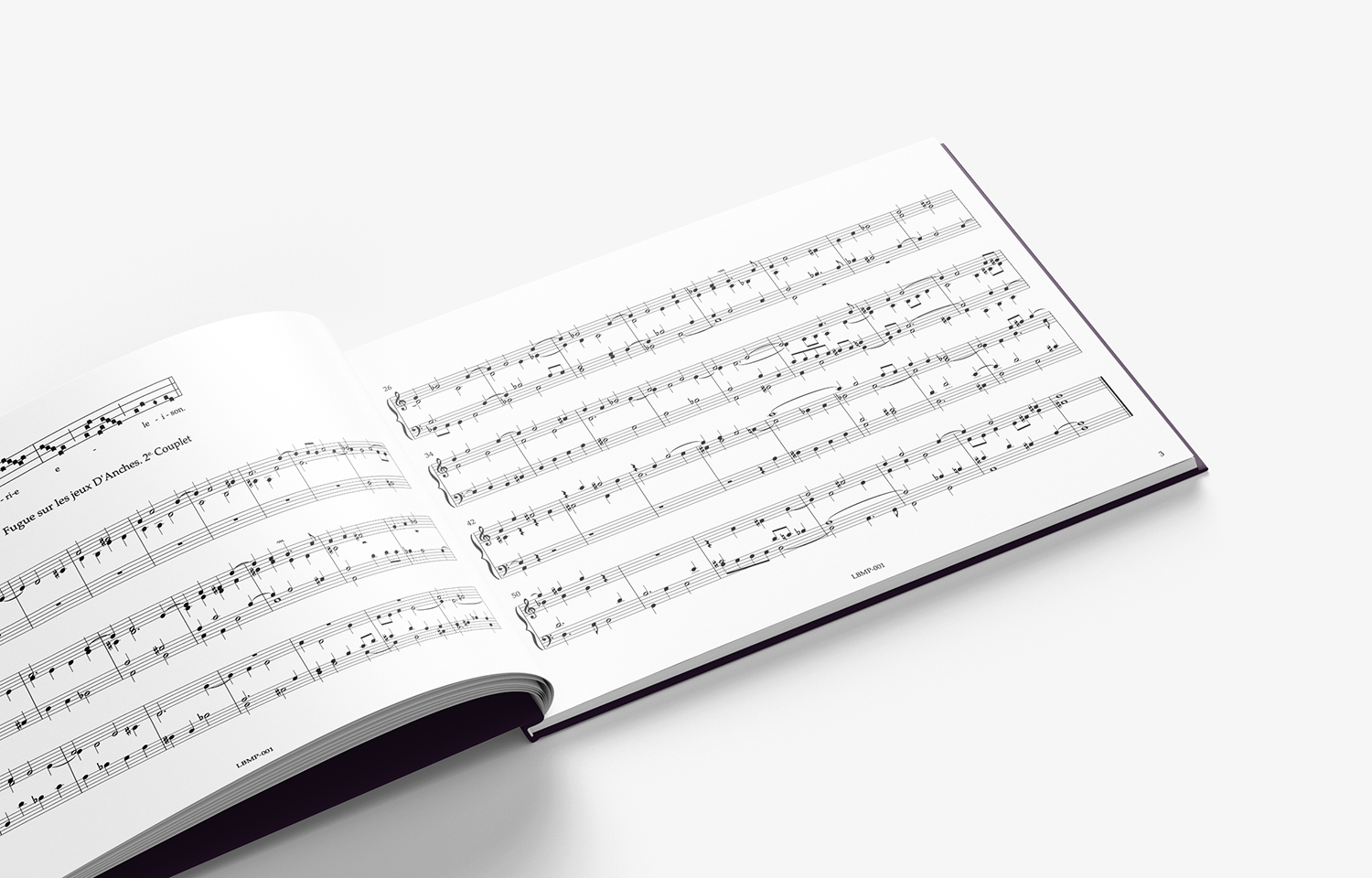

As an organist myself, I value the edition’s landscape format, the clarity of the print and its relatively spacious layout which leaves space for the insertion of fingering! I do, however, regret that the margin on the binding edge is not a little more generous in order to provide easier reading of those parts of the pages. However, above all I value Couperin’s music, of which we now have a newly-authoritative edition we can use with re-booted confidence and understanding – an edition underpinned by no little editorial knowledge, skill and sheer love.I honestly think that this is the publication that those who play the French Baroque organ repertoire have been needing for decades.

EARLY MUSIC REVIEWS

Andrew Benson-Wilson

François Couperin is one of those composers that is well-known to organists, although many of them will not know much about his non-organ compositions. He is also known to many non-organist music lovers, although many of them will not know much about his organ music. Like many organist-composers, Couperin’s organ works were published very early in his musical career, before his move into court circles and a compositional career mostly devoted to harpsichord, chamber and sacred vocal music. His father, Charles, was organist at the church of Saint-Gervais in Paris, just north of the Île de la Cité and the river Seine, where he had succeeded his brother Louis, the founder of the Couperin musical dynasty and a distinguished composer and performer. Charles died when François was about 11, specifying François as his successor. As Jon Baxendale discusses in his excellent Background Notes, this was the result of the practice of survivance, where an organist was able to specify his own successor, leading to such ‘family business’ situations. In the case of the Couperin family, the role remained in the family well into the 19th-century. François formally succeeded to the post when he reached the age of 18, the intervening years being taken up by increasingly intense training for his forthcoming role, during which he was paid a proportion of the stipend by the church authorities.

François Couperin was born 10 November 1668, and this 350th anniversary year is an apt moment for a new critical edition of his Pieces d’orgue. This collection of liturgical organ works dates from 1690, when he was 22. It consists of two Mass settings, with examples of the organ pieces that would have been played during the Latin Mass, most of them to be played in alternatim with the choir. One setting is intended for use in parish churches (à l’usage ordinaire des Paroisses Pour les Fêtes Solemnelles), the second for convents or abbey churches (Convents de Religieux et Religieuses). The latter setting is less complex than the first, and was written for a smaller organ, an indication that musical standards would have been higher in the parish churches, with a professional organist, than in the convents where the organ was played by one of the inmates.The background notes (in English and French) explore the background to the composition, existing and lost source material, and performance practice including ornamentation, registration and a brave attempt at explaining the all-important concept of notes inégales an aspect of rhythmic flexibility that is key to performance. The specification of the Saint-Gervais organ is included in its 1714 four-manual state – it was later enlarged to five manual, with the addition of a Bombarde division. As well as representing Couperin’s own organ at the time of composition, it also acts as an example of a classic French organ in an important Parish or city church. There is also a conjectural two-manual specification suitable for the Messe pour les Convents. The appropriate chant settings are also included, allowing for performance within a liturgical context. Detailed information about registrations includes tables of comparative examples for each separate piece, including comments from the period on the appropriate playing style for each registration. One performance aspect that isn’t discussed (or one that I have missed) is the very large left-hand stretches in some of the pieces.

One of the reasons this new critical edition is so important is that includes a serious look at the sources, a major issue with the Pieces d’orgue. The music was only ever published in manuscript, leading to several issues of authority and accuracy. There is only one surviving copy of the original, so secondary sources become important as a check against inaccuracies. There are four known sources and two that are lost. Included in the Notes is a useful flowchart showing the possible links between the various sources. At the back of the volume is a lengthy list of all the textural differences.The print is clear, although it is not as large as some modern organ music editions. From a practical point of view, I only have two slight concerns about this edition. One is that the paper appears to be rather absorbent, so might not be quite so immune from the sorts of incidents that can wreak havoc with music, not least damp. But it is matt and non-reflective, which can be a problem with glossy paper. The other concern is the layout of the music on the page. There is a larger margin on the outside edge of the page than at the inner binding edge, with the result that, on organ music desk, the music tends to fold into the shadow of the centrefold, as shown in the image below. Repeated bending of the spine will probably solve this, but at some possible risk to the stability of the spine. As can be seen from the example page, in the alternatim verses, the relevant chant is included, in chant notation, before each piece. You can also see an example of an editorial intervention, here showing an alternative reading of a passage.

A few of the pieces with pedal plainchant include an additional version with the pedal part put into a separate stave. Only in the two double pedal pieces is this really needed – for example, the Sanctus of the Parish Mass where the two pedal parts are to be played an octave lower which can be confusing in two-stave format. I personally find it much easier to play the tenor pedal line in, for example, the opening Plein chant du premier Kyrie, en taille, from a two-stave format rather than with the pedal put into a third stave.This is an important addition to the organ literature.