By Jon Baxendale

(This post is adapted from the preface of Nicolas Lebègue, Pièces de clavecin et d’orgue, ed. J Baxendale (Tynset, Lyrebird Music, 2025).

While the port de voix is an ornament associated with French baroque keyboard music, we know little about its use before the mid-1660s, when Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers first mentioned it in his Livre d’orgue (Paris, 1665). Although most treatises utilise ports de voix, D’Anglebert (1689) and Le Roux (1705) ( likely inspired by the earlier composer)), prefer cheute and chute, respectively. Its roots lie in vocal music, and if we follow the advice Nivers offers in his first organ book (1665), singing treatises should be consulted for its execution because ‘in these instances, the organ must imitate the voice’.1

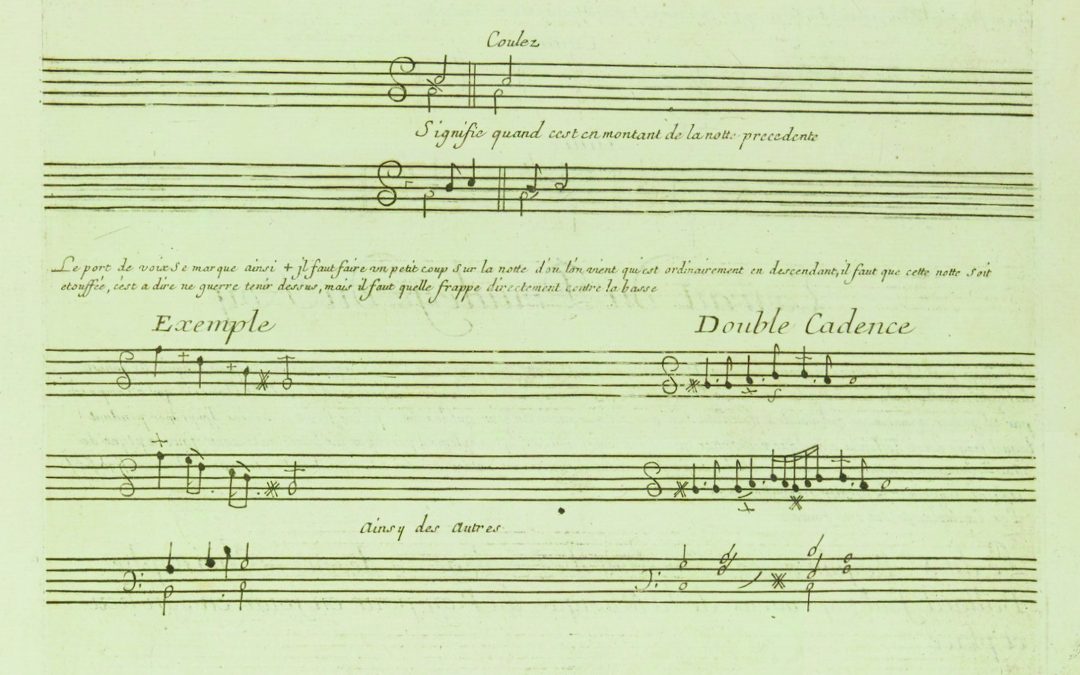

An early discussion of the port de voix appears in Bertrand de Bacilly’s Remarques curieuses sur l’art de bien chanter (3/1679, 137–161), where he states that the ornament is divided into two categories: the port de voix plein (also known as véritable) and the demi port de voix. The latter has two subspecies: the port de voix glissé (also called coulé) and the port de voix perdu. In both forms, it is common to repeat the child note (Bacilly, 3/1679, 141). In a port de voix plein, the voice sustains a lower, pre-beat note before rising to the parent note, at which point it performs a doublement de gosier. The port de voix glissé involves a gentle glissando toward the parent note, which should not be delayed; the port de voix perdu begins by splitting the preceding note and sustaining it for nearly the entire duration of its parent before executing a doublement de gosier and coming to rest (more on this below).

As a keyboard ornament, the port de voix’s realisation is found in most tables, where liaisons are used to indicate that the child note is sustained while its parent is struck. Rameau (1731) is more organised: he eliminates the liaisons and assigns child and parent notes to separate parts to demonstrate the ornament’s mechanics. Nivers (Paris, 1665), Raison (Paris, 1688), and Saint-Lambert (Paris, 1702, Chapter XXIV) also provide verbal explanations, with the former indicating that the first note should be held momentarily while the second is played. Saint-Lambert concurs: ‘[…] one should not lift the fingers while touching [the keys] but wait until the second of the two notes is struck before lifting the finger that touched the first’.2 He explains that the essential ingredient is splitting the child note, which finds parity in the ornament tables of both Nivers and Chambonnières (Paris, 1670).

Whether or note a port de voix should be considered a pre-beat ornament has been a topic of debate since it was first used in keyboard music, although there is scant evidence in historical sources to suggest otherwise. One of the more enlightening explanations can be found in a curious allemande from Nicolas Gigault’s Livre de musique (1682), where he freely incorporates ports de voix ‘to give an idea of their application and the manner of applying them to all other kinds of pieces.3

Ex. 01: Gigault’s Allemande par fugue with his realisation of the port de voix.

Gigault’s example is fussy and unlikely to have been intended for performance. Nevertheless, the placement of the child note aligns with all known ornament tables and clearly indicates a pre-beat ornament. While some commentators as far back as Saint-Lambert interpreted D’Anglebert’s examples as on-beat ornaments, there are few reasons to think he defied a convention that lasted for more than a half century. Insdtead, they likely misunderstood D’Anglebert by placing too much emphasis on his explanation’s appearance. Indeed, the three species of ports de voix he demonstrates are no different from the example in Chambonnières, with the misinterpretation stemming from imprecise spatial positioning and an unrefined notational orthography.

Guided by the renowned arbiter le bon goût, the nuances necessary for executing the port de voix are not suited for inexperienced musicians. This may explain why some composers as Nicolas Lebègue completely omits the ornament from his books. Indeed, Lebègue appears to recognise that more amateur musicians were likely to purchase his publications than professionals, as he notes that he tailored the second organ book (1682) to meet their ‘mediocre’ needs:

Perhaps we might not observe as much sophistication and complexity as in the first [book] since Monsieur Le Begue aimed to be intelligible to all and was even compelled to abandon the passion that usually accompanies his playing, given that very few people can succeed at it.4

Therefore, it should surprise none that an ornament that relies primarily on abstract taste and a feeling for melody and the line would be overlooked.

We also see the inference of ports de voix when considering the pincement.

While the pincement is straightforward to interpret, its combination with a port de voix is used by some composers to great rhetorical effect, such as bar 4 of Lebègue’s ‘Courante gay’ (Suite I), where an upwardly rising phrase, comprised of a dotted-crotchet–quaver rhythm, features a pincement on each metrical foot. It moves to a high point in the strain, and adding varying ports de voix would increase the phrase’s rhetorical tension.

Ex. 02: Nicolas Lebègue: ‘Courante gay’ from Les Pièces de Clavecin (1677, no. 4)

The issue is that no harpsichord preface demonstrates this combination of ornaments. However, if we look to organists, Jacques Boyvin (Paris, 1690) is specific about its execution. He states that in ascending figuration, a pincement must be prefixed with a port de voix and that ‘this note, though dissonant, must fall upon the beat’.5 If this was Lebègue’s preference, his dances might be rich in examples of ports de voix, even if they are restricted to compound ornaments.

Boyvin’s rubric is vague regarding the temporal placement of the pincement. However, considering the ports de voix glissés and perdus discussed by Bacilly, where the doublement de gosier comes into play, various renderings of the ornament become possible. Bacilly (3/1679 196–197):

The third ornament [doublement de gosier], which denotes a long syllable and is never executed on any short syllable, repeats the same note with the throat. It is done so quickly that it is hard to hear whether there is one note or two. This is easily performed on the violin with the bow and is commonly referred to as animer, that is to say, bringing mouvement, to which this ornament greatly contributes. Without it, airs would be soulless and would become tiresome.6

The type of repetition Bacilly advocates would be challenging to achieve successfully on keyboard instruments. Yet, substituting the doublement de gosier with a pincement would produce the same rhythmic effect if the ornament is performed rapidly. While Boyvin goes a long way in explaining the port de voix-pincé arrangement, it is likely that solutions were based on the port de voix glissé and the port de voix perdu. Thus, the following guidelines might be drawn upon when executing the ornament.

- The port de voix glissé is more appropriate for shorter note values, which may proceed to its parent and an immediate

- The port de voix perdu is more effective for longer notes and may be held for up to the total value of its parent before the pincement is executed.

- The pincement should be performed so rapidly that it is almost imperceptible.

- The type of ornament chosen may depend on the required rhetorical effect.

In either case, the pincement plays the role of Bacilly’s doublement de gosier.

In this instance, a case has been made that ports de voix-pincé combinations are discrete ornaments, with independent rubrics far removed from the plain pincement. If so, the ornament Bacilly describes (and Boyvin demonstrates) is a more complex construct that requires the connoisseur’s understanding of le bon goût to perform effectively.

• • •

Bibliography

Jean-Henri D’Anglebert, Pieces de clavecin (Paris, 1689).

Bertrand de Bacilly, Remarques curieuses sur l’art de bien chanter (Paris, 3/1679).

Jacques Boyvin, Deux livres d’orgue (Paris: 1690 and 1700); ed. Jon Baxendale (Tynset: Lyrebird Music, 2022).

Nicolas Gigault, Livre de musique (Paris, 1682).

Nicolas Lebègue, Les Pieces de Clavessin (Paris, 1677).

Guillaume-Gabriel Nivers, Livre d’orgue (Paris, 1665).

- ‘[…] qu’en ces rencontres l’Orgue doit imiter la Voix.’

- ‘[…] il ne faut pas lever les doigts en les touchant, mais attendre que la second des deux Notes soit touchée, pour lever le doigt qui a touché la premiére [sic]’.

- ‘[…] pour donner l’idée & l’usage de les appliquer à toutes autres sortes de pieces’.

- ‘On n’y verra pas peut Estre tant d’Erudition et de recherches que dans le premier, parceque Monsieur le Begue a voulu se rendre Intelligible à tous, Et il a esté mesme contraint d’abandonner ce grand feu qui accompagne dordinaire son Jeu, d’autant que très peu de personnes y peuvent reüssir’.

- ‘[…] cette notte quoy que dissonante doit frapper contre la basse’.

- ‘La troisiéme marque de longue, & qui ne se pratique sur aucune syllabe bréfve, eft le Doublement de la mesme Notte qui se fait du gosier, si promptement, qu’à peine on s’aperçoit si la Notte est double, ou si elle est simple, ce que l’archet du Violon exprime assez bien, & ce que l’on nomme vulgairement animer, c’est à dire donner la mouvement, à quoy cet ornement du Chant contribuë beaucoup, & sans lequel les Airs seroient sans ame, & ne seroient qu’ennuyer’.