By Jon Baxendale

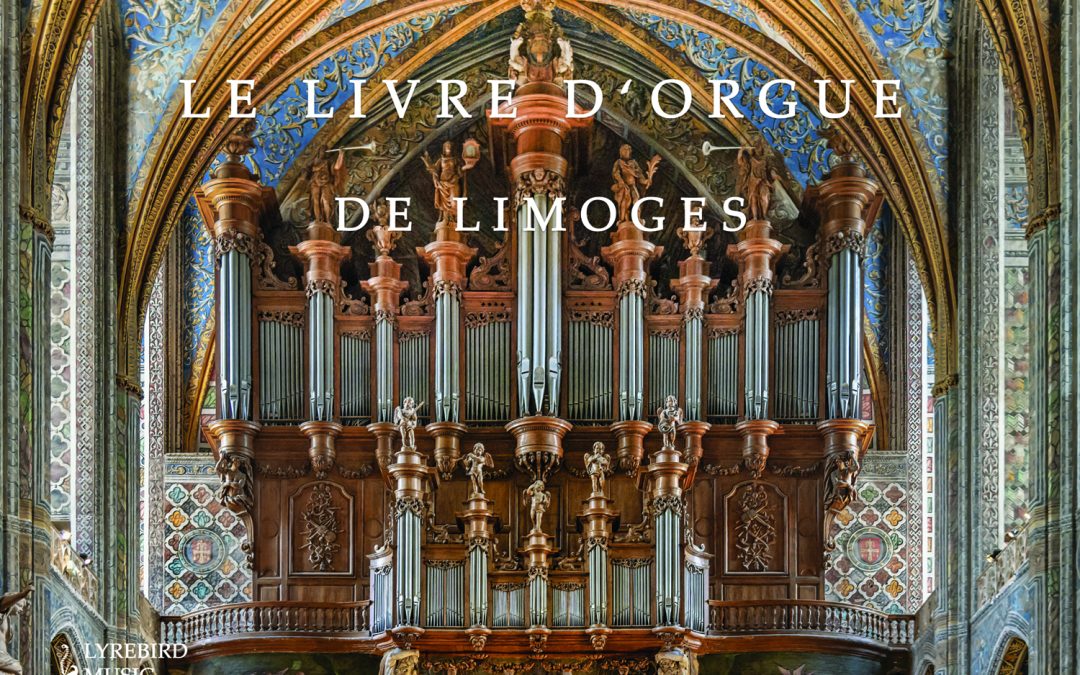

Le Livre d’orgue de Limoges (hereafter Limoges) has been housed in the Bibliothèque francophone multimedia in Limoges (F-LG, MS 255) since being donated to the library in November 1990 by Christian Gaumy, a local bibliolater (Marissal, 2004, 121); previously, it had been in the library of a chateau in the Limoges region (Marissal, 2003, 8). It is in upright format with 50 pages of twelve hand-rastered staves. A further leaf, now separate from the book, contains a fragment of a duo in Tone VI, though much of the page has been excised, as have the outer margins of what are now pages 37–40. Numbering is seriatim and in the hand of the scribe (hereafter Scribe L) until page 26. Subsequent page numbers are provided in pencil, and we must assume these to have been the work of a librarian. All but two pages contain music, with blank rastered pages occurring at 28 and 35; the lower portion of page 49 consists of a single-line melody in Tone VIII, while the following page has its variant set to the Franciscan memorial text Cælorum candor splenduit. The cover board is marbled in a style fashionable for inexpensive relié bindings in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, though there is no evidence of a leathered spine. The front board has suffered considerable deterioration, with part of the marbling torn away along the spine in the upper left quadrant; further damage begins in the lower right and extends to the centre of the front cover. Pest damage has expunged an area along the board’s lower edge, affecting each leaf but not the back board. It might be that similar reasons occasioned the missing margins of pages 36–40. Water damage is present in the upper quadrant of the first seven leaves and the right-hand margin of fols. 1–17.

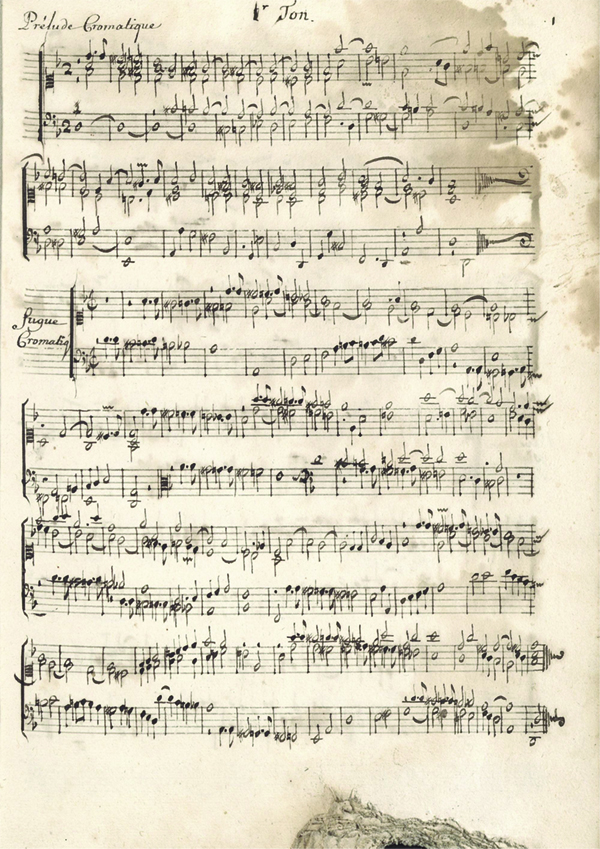

Fig. 01: The first page of Livre d’Orgue de Limoges demonstrating water and pest damage.

The script is consistent and lacks variances in ink pigmentation or quill size, suggesting copying occurred quickly. Notation is of a professional standard: the hand is flowing with few errors, and corrections were undertaken by elongating noteheads where possible, adding or extending beams when necessary, erasing an error by painting it with water to dilute the ink or scratching away the surface. Fifty-four errors were corrected; otherwise, there are few wrong notes.

The library has dated the manuscript 1710–1725, which it probably bases on the genres and style of its contents. They reflect pieces popular among liturgical composers until after the publication of André Raison’s book of 1714. Significantly, only five liturgical organ books were published between that date and the appearance of Le Clerc and Beauvarlet-Charpentier’s subscription series of the 1780s.1

Despite retaining two archaic notational practices (augmentation dots in adjacent bars and minims on barlines to replace tied notes), the music is copied using surprisingly modern conventions. Most apparent is the use of the F4 clef, which French harpsichord composers favoured until c. 1713 when François Couperin’s first book of Pièces de clavecin was published. However, organists still preferred F3, and the standard bass clef did not appear in known sources before Michel Corrette’s 1753 Nouveau livre de noëls; even then, F3 clefs were to reappear in his later publications. Scribe L’s policy towards accidentals is also surprisingly contemporary. Traditionally, chromatically altered notes were not repeated in a bar unless accordingly marked, and this approach is retained in both harpsichord and organ sources until Michel Corrette’s 1750 Deuxième livre de pièces d’orgue. However, the old practice continued, as demonstrated by Corrette’s noëls, his Troisième livre de pièces d’orgue (1756) and his harpsichord collection IV. Livre des Amusemens du Parnasse (Paris, 1762). Cancelling accidentals are also revealing since they, too, follow modern conventions. In most sources, this entailed cancelling a sharp with a flat symbol and so forth, and the use of natural symbols in their place is unknown in organ sources before Corrette’s Deuxième livre de pièces d’orgue of 1756. In Limoges, natural symbols are preferred except for a single dialogue (no. 42, bars 103 ff.). Another intriguing feature is that pieces in Tone I have been altered to use a B-flat as their key signatures, effectively making the key D minor––an emendation unknown in French keyboard sources before Balbastre (Paris, 1770). A similar treatment is given to pieces in Tone II, which reads as G minor. The lack of printed sources after 1756 makes it challenging to pinpoint when strictly diatonic key signatures appeared in organ sources, though Corrette (Paris, 1756) and Daquin (Paris, 1757) retain church tone signatures. However, the first point at which Limoges’s novelties are uniformly found in printed sources is in Le Clerc’s Journal de pièces d’orgue in 1780, which could mean Limoges was copied much later than the library’s estimation. Because of these innovations, we might reasonably conclude its date to be between 1770 and 1780.

The problem is that the manuscript’s content would have been considered archaic by the 1770s, and this type of music should, by rights, not have been included in such an anthology. We must not, however, allow this to mislead us. The intense compositional flurry of the late seventeenth century had become stagnant in the first decade of the eighteenth. It was probably this dearth that precipitated Christophe Ballard’s 1711 re-release of Grigny’s Livre d’orgue. Ever the businessman, Ballard would have been only too aware of this gap in the market, and Grigny’s publication would have helped to fill the void. After Raison’s second book of 1714, only Michel Corrette significantly contributed to liturgical organ music. Thus, given the absence of contemporaneous printed material, it is a relatively straightforward matter to understand how and why the manuscript’s contents were chosen.

While it would be desirable to identify the composers of the unicum pieces, few versets are sufficiently long enough to draw conclusions with any authority. We may be sure that nos. 3–6, a suite of versets on the hymn Ave Maris Stella, were from the same pen, and this is partially confirmed by a rare feature in French organ sources, where the beginning of the solo in ‘Tierce en Taille’ precisely mirrors the dessus of the preceding ‘Récit de nazard’.

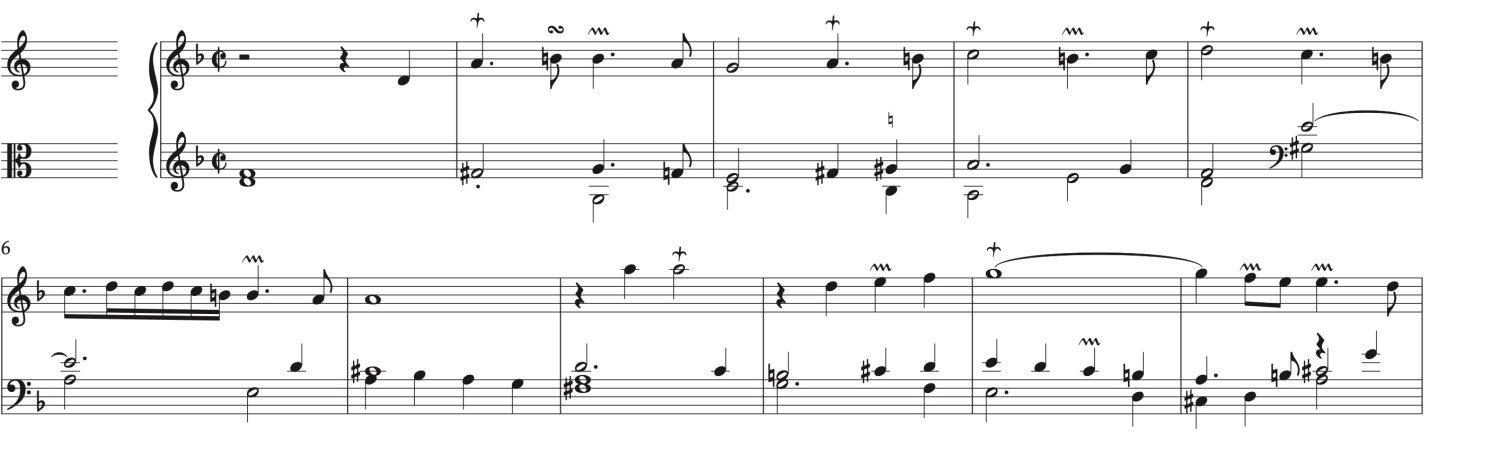

Ex. 01a: Opening of the anonymous ‘Récit de Nazard ou de Tierce

Ex. 01b: Opening of the anonymous Tierce en Taille (F-LG, MS 225)

The tierce en latter’s opening, in which the first chord briefly moves to a #7/4/2 harmony before returning to the tonic, is a sequence Raison uses in several versets of his 1688 publication. However, we should also note that it is also a standard rhetorical cliché found in much keyboard music of the Grand siècle.2 Similar figurative treatment is found in two duos (nos. 7 and 16), and since we know the latter is by Raison, we may conjecture that he also penned the former.

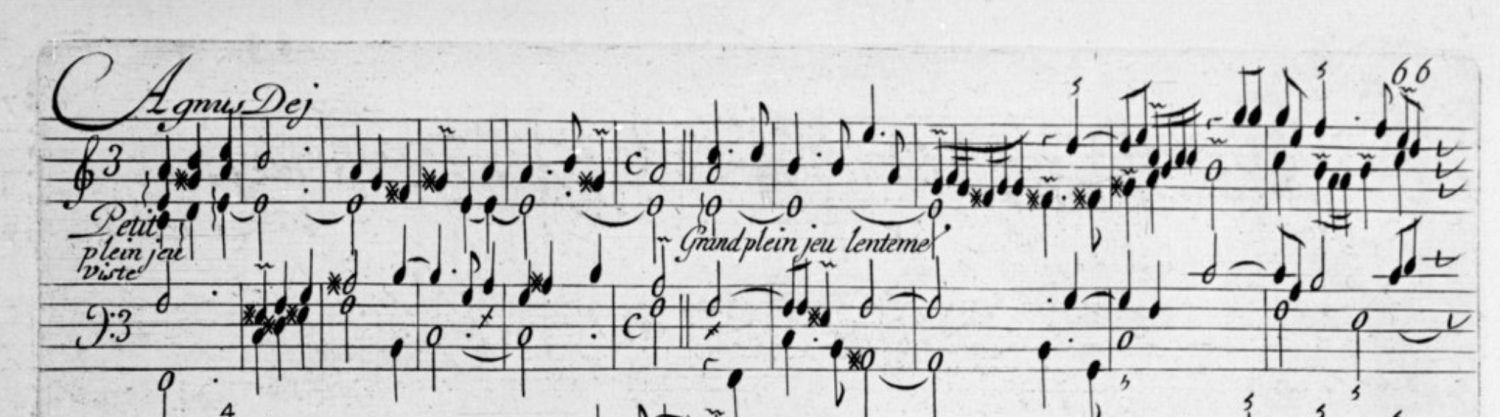

Ex. 02: Opening of the first Agnus Dei, André Raison, Messe du Troisiesme Ton (Paris, 1688)

Other similarities may be drawn between nos. 17–19 and Raison, particularly in the passepied-like ‘Dialogue’ (no. 18), which is reminiscent of the syncopated phraseology of the fifth Kyrie (Tone I) in Raison’s 1688 publication. However, while he provides an ouverture-like coda, the switch from a lively 3/8 to C in Limoges is more subtle. The device is typically used in airs de cœur to allow the final cadence to end on the correct metrical foot, though Louis-Nicolas Clérambault – who is primarily remembered for his vocal music––also uses it to significant effect in the allemande of his second harpsichord suite (1702/4). Raison also uses the device in the closing couplet of the same Gloria, though since this lacks the same elegance and technical competency, we might rule him out as a composer. Elsewhere, the chromaticism of the opening prelude and its accompanying fugue is reminiscent of Gilles Jullien’s ‘Fantaisie Cromatique’ (no. 24), not only in the preparation and resolution of its angular dissonances but also in a melodic content that is arranged around a descending tetrachord.

Ex: 03: Opening of the anonymous ‘Fantaisie Chromatique’ in Limoges, demonstrating a similar chromatic treatment to Julien’s ‘Fantaisie Cromatique’.

Again, this is a standard cliché found in keyboard music including Gaspard Corrette (no. 47) and was a popular technique employed by composers of both vocal and ensemble works. ‘Trio a 3 claviers’ (no. 13) is reminiscent of Jacques Boyvin in terms of figuration, imitative phraseology and a tendency towards parallel writing for episodic material. The third part is marked ‘Une 3e main Sur la Tierce au grand Corps’ and, if we scrutinise Boyvin’s ‘Trio pour la pedalle’ (Premier livre d’orgue,Paris, 1690, 75), we see correlations in his use of tessitura, ornamentation and figuration. For the same reason, similar conclusions may also be drawn from ‘Trio’ no. 39.

One final parallel may be drawn between Fugue (no. 9) and Jean-François Dandrieu’s Dialogue, which closes the Magnificat suite in Tone I (1739) insomuch as both enjoy a rhetorical use of pervasive rising chromatic figuration (bars 26 ff., Limoges and 28 ff., Dandrieu). However, Dandrieu restricts its use to the lowest voice, while the fugal nature in Limoges allows for a more expansive and convincing treatment.3

• • • •

Bibliography

F-LG, MS 255, Le Livre d’orgue de Limoges.

Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet-Charpentier, Douze Noels (Paris, 1782).

Claude Balbastre, Recueil de noëls (Paris, 1770).

Jacques Boyvin, Premier livre d’orgue (Paris, 1690).

Guy Marissal, Manuscrit de Limoges : Magnificat, Kyrie, Gloria, Ave maris stella, Pange lingua, Liner notes, Disque Lira d’Arco, 2003, Sagittarius, M. Laplénie CD (511).

_____, ‘The Manuscript of Limoges’, The Organ Yearbook, vol. 33, 2004, pp. 121–125.

- This number discounts four books of noëls and Charles Piroy’s secular Pieces choisies (1712), which are of little relevance to this study.

- Raison uses this sequence three times: the first Kyrie and Deo Gratias of Messe du Premier Ton and the first Agnus Dei of Messe du Troisiesme Ton.

- I am grateful to David Ponsford for this observation. Note that the 1739 date of Dandrieu’s publication does not support my argument that Limoges was copied late in the eighteenth century. Dandrieu’s book was posthumously published by his sister, Jeanne-Françoise, and since some of its music is adapted from Pierre Dandrieu’s revised book of noëls (c. 1727), we might assign it an earlier provenance.