By Francis Knights and Jon Baxendale

i. History

The circumstances surrounding the compilation of My Lady Nevells Book (hereafter, LNB) are unclear. However, it has been assumed that it was commissioned by Sir Henry Neville or his wife, Elizabeth, the ‘ladye’ of the book’s title. Henry was the younger son of Edward ‘the deaf’, a courtier to Henry VIII who ultimately fell under suspicion of treason and was executed in 1539. Neither of his sons was implicated: Edward inherited the Abergavenny baronetcy from his uncle, and his brother Henry––godson to the king––was returned five times as Member of Parliament for Berkshire, where he maintained several properties. He married the widow Elizabeth Doyley (1541–1621, née Bacon), an independently wealthy woman who had inherited estates in Berkshire from her first husband.

Elizabeth was daughter to Sir Nicholas Bacon and half-sibling to philosopher Sir Francis Bacon, (later Lord Chancellor, like his father) whose natural mother died when she was eleven years of age. Sir Nicolas subsequently married Anne Cooke, the daughter of Anthony Cooke, who had been Edward VI’s tutor, and who was a believer that women should be as well educated as men. Therefore, it is likely that Elizabeth acquired from her step-mother those qualities normally afforded male children, which would have included, among other accomplishments, an education in classical and modern languages, and undoubtedly music.

In 1593, Sir Henry Neville died, and Elizabeth married Sir William Peryam. She was the dedicatee of the two-part canzonettas (1595) by Byrd’s pupil Thomas Morley, whose wife had been in her service. As Oliver Neighbour points out (2012, 6), Elizabeth – who was about the same age as Byrd – must have been either a capable keyboard player or liked to hear someone with considerable abilities at the keyboard play: she was probably quite familiar with Byrd’s music, if not the man, himself. At the time, he lived at Harlington, a village close to Windsor Castle where Sir Henry had occupied several posts that included Steward of Mote Park in Windsor (1557) and High Steward in Reading and New Windsor (both 1588). Nevell was also returned as Member of Parliament for Berkshire on five occasions after 1553. 1

A note pasted on fol. iir of the manuscript tells us something of its history. It reads:

This book was presented to Queen Elizabeth by my Lord Edward Abergevennye [sic] called the Deafe; the queene ordered one sr or mr North one of her servants, to keepe it, who left it his son, who gave it to Mr Haughton Atturny of Cliffords Inn, and he last somer 1668 gave it to me; this mr North as I remember mr haughton saide, was uncle to the last Ld North.

M Bergevenny

Harley (2007, 11) suggests that the M of the signature is Mary Neville (née Gifford), the wife of George, the 11th Baron Abergavenny, which allows us to date the note from before her death in 1696. 2 However, there are no reasons to dispute the sequence of events she described, although her narrative contains a number of errors which Neighbour (2012, 7) corrects. If the book was given to Elizabeth I, it could not have been by Edward ‘the deaf’ since he died in 1589, two years before it was copied. It is also unlikely to have been his son, also called Edward, since there is no reason for Mary Nevell to give it to her brother-in-law’s son. However, there is a third candidate in the son of Sir Henry Nevell, who lived in a house in the Savoy in London. Upon his death in 1595, he bequeathed the house and its contents to his younger son, also called Edward. Two years later, Elizabeth Nevell remarried. If her book had been left in London, she might have either forgotten about it or gave the book to Edward, who then gave it to the queen.

The ‘mr North’ to whom Mary Bergavenny refers is probably Sir Henry North of Wickhambrook and Mildenhall (1556–1620). If so, the son who later received the book would have been Sir Roger of Mildenhall and Great Farnborough (1577–1651). According to Harley, there are no records of an attorney by Haughton’s name at Clifford’s Inn, though he makes several viable suggestions. It is unclear what happened to LNB afterwards: John Hawkins briefly described it in 1776 (iii, 288), but little more is known before it turned up in Charles Burney’s collection, who described it in his 1789 A General History of Music (iii, 91). Upon Burney’s death in 1814, it was auctioned as lot 561 by White of Storey’s Gate, who was tasked with the sale of Burney’s library. It was purchased by Thomas Jones for £11 0s. 6d. In 1826, it was auctioned again and sold as lot 342 to Robert Triphook, a bookseller of St James’s Street. When he closed his business in 1833, the manuscript was not listed in the sale catalogue. Harley (2007, 12) suggest that it had been sold back to the Neville family sometime before then. However, in 1841, the musicologist Ernest F. Rimbault wrote that he had seen it in the possession of Lord Braybrook, a descendent of Sir Henry Nevell (Neighbour, 2012, 8). Twelve years later, though, Rimbault claimed that Triphook had sold it to Lord Abergavenny. It remained the property of the Abergavennys until 2002 when the British government accepted it in place of inheritance tax. LNB was subsequently allocated to the British Library.3

ii. Description

LNB is unique among those late Tudor and early Jacobean manuscripts that have come down to us since it is devoted entirely to a single composer, William Byrd. Like many music manuscripts of its day, it is in oblong format with covers measuring approximately 206 x 282 mm. 4 Its binding is typical of the late sixteenth- and early-seventeenth centuries, with tooled leather boards containing a gilt flower motif, a central cabochon cartouche and ornate corner pieces with scrollwork shells.5 The upper text block is gauffered with a vine-leaf pattern. Both front and back covers are identical, in brown morocco and decorated with punchwork of a repeated quatrefoil pattern for the exergue and ground, and embossed titling is placed centrally towards the head. Remnants of black, white, red and green colouring are visible and provide an idea of the cover’s original appearance. Although the boards display no heraldic association, a separate leaf bound into the book (fol. iv–r; see the image at the beginning of this book) contains the illuminated arms of the Nevell family. These bear tinctures which indicate a date from before c. 1626, when cross-hatching became the standard means of representing heraldic colours. In consultation with the College of Arms, John Harley ascertained that these were the arms of Sir Henry Nevell of Billingbear (c. 1520–1593). If so, then the ‘Ladye Nevell’ of the title must be Elizabeth (née Bacon), who became Sir Henry’s third wife in c. 1578 (Neighbour, 2012, 2).

Pastedowns and endpapers are of moiré silk. While this was popular as a fabric since the early sixteenth century, it is not original and appears to come from 1781, when the book was rebound. The date is found along the front board’s back tail and is part of the binder’s signature. Though partially obscured by the endpaper and turn-in, the date is easily decipherable, although the remainder is not.6 The rebind’s extent is visible along the turn-in of the head, tail, fore-edge and corners of each cover, with a lighter leather used to patch worn areas. Whether this later work included an alteration of the covers cannot be said, although there are no visible signs of any changes apart from centrally placed holes in the leather about 5 mm from each board’s head and tail. They are approximately 8 mm in diameter and possibly indicate that the repair included removing clasps or ties of some sort.

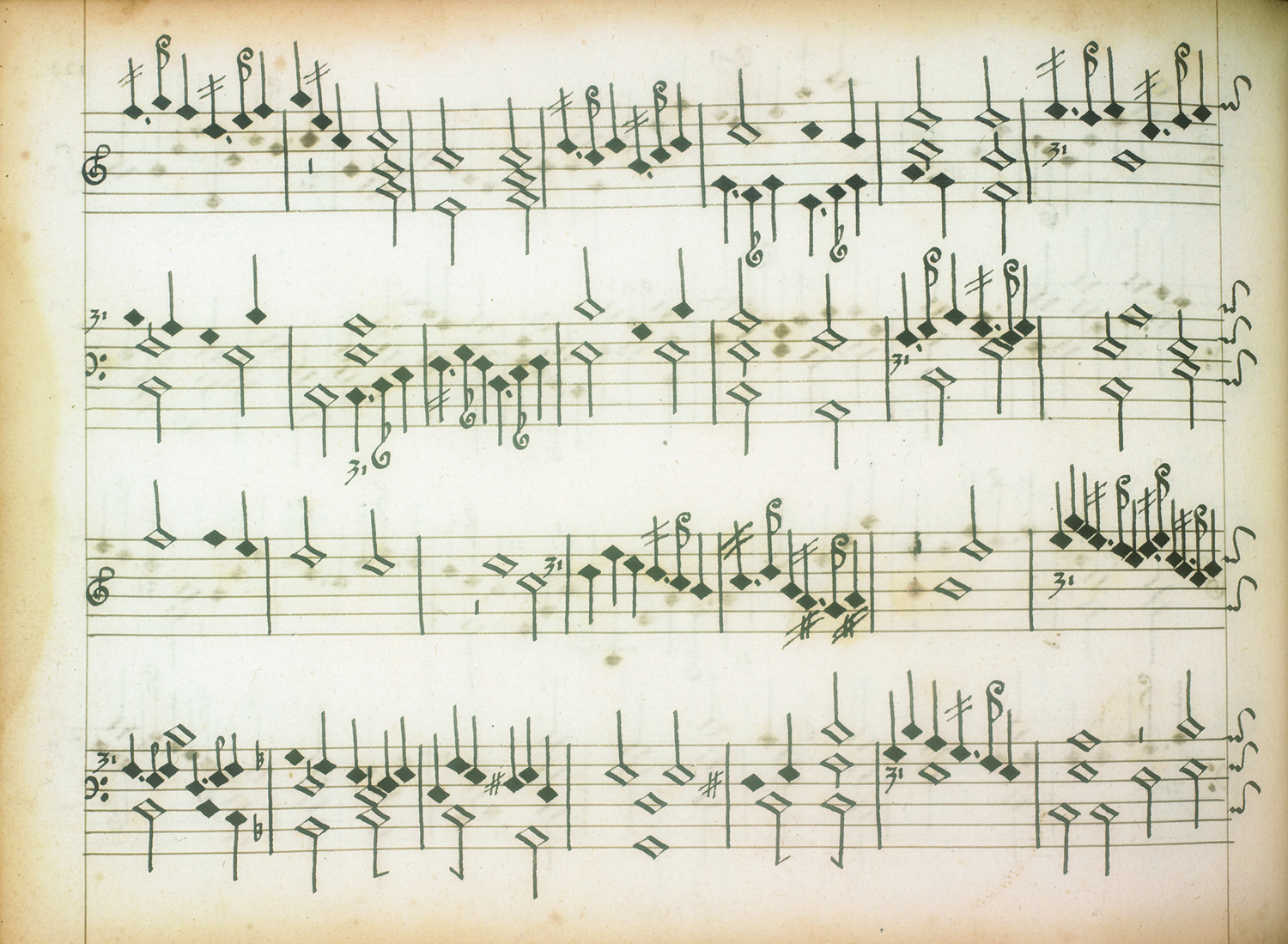

Like many Tudor and Jacobean keyboard sources, the music is organised so that the upper staff is reserved exclusively for the right hand and the lower the left, with the music carefully distributed using ‘directs’ when a line crosses the staves. Typical of early English notation, stems point upwards unless the music is polyphonic or uses chords. The book is foliated, with each page containing two systems of six-line staves––a common feature of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English keyboard music––which restricted the need for too many variable clefs and leger lines. Left and right margins are uniformly ruled at c. 20 mm and while upper and lower margins vary, the distance from the staves is usually around 20 and 30 mm, respectively. How the staves were ruled is unclear: a similar distance between lines is maintained throughout the manuscript, but this is not always uniform and their varying lengths, whereby some cross the margin lines and others fall short, suggests that each was drawn independently. The pigmentation of ink for the staves is of a lighter colour than for either notes or titles.

Space is carefully conserved with each piece immediately beginning on the next system, which condenses the music into exactly 24 gatherings. An index table was prepared as a final gathering and spaced over three sides on fols. 2 and 3v, although only the first two have entries. These were entered on fol. 2v using horizontal lines as guides, although on fol. 2v., the copyist relied on either the impression of the text of its recto side or the degree of ink seep-though that might be expected of bond paper of this quality. It cannot be said if he overestimated the space his index would take, but it nevertheless raises the tantalising question concerning whether or not more music remained to be added which was not, perhaps because of time limitations, ultimately included.

At the end of the index (fol. 193v), a colophon tells us when copying was completed. It reads:

At the end of the index (fol. 193v), a colophon tells us when copying was completed. It reads:

finished & ended the leventh day of September: in the year of our lorde God • 1591 • and in the • 33 • yeare of the raigne of our sofferaine lady Elizabeth by the &c God queene of England: &c. By me Jo: baldwine of windsore : ––

–– : laudes deo : ––

Its author was John Baldwin, singer, composer and music copyist.7 Yet, unlike composers such as William Byrd or John Bull, whose stature made them celebrated beyond their immediate musical circles, it is difficult to glean much information of the man or his activities. His date of birth is unknown; the Cheque Books of the Chapel Royal inform us that he died in 1615. Brennecke (1952, 33) states that he was ‘admitted a lay-clerk, a singer of tenor parts, at St George’s Chapel Windsor in 1575’. However, there is little surviving evidence to corroborate this since records for that year have now deteriorated to the point of illegibility. Baldwin is mentioned in the chapel rolls from 1586 to 1592, during which time he received payments for copying music in 1586, and between 1588 and 1591 for reading the Epistle and saying obits (Welch, 2017, 11–16). In March 1593, he was admitted as an honorary member of the Chapel Royal and promised the next vacant place as a tenor. Baldwin was elected as a full Gentleman on 20 August 1598 (Ashbee and Harley, 25). It is not known whether or not he copied music for the Chapel Royal. However, like most royal institutions, records for the period are thorough enough for us to learn of petty squabbles among clergy and musicians alike. Baldwin is not mentioned as the recipient of payments for anything other than singing, which suggests he copied music for his own purposes.

It is unlikely that Baldwin continued to serve St George’s after 1598 since their rolls contain no further mentions of his name. Rates of pay and service conditions at the Chapel Royal were good, and the status of its members placed them on a higher level than cathedral lay-clerks and minor canons. In comparison with St George’s, where his stipend had amounted to ten pounds per annum with additional fees (Welch, 2017, 11–14), daily fees at the Chapel Royal amounted to seven and a half pence, to which were added travel and boarding expenses.8 Until 1604, this amounted to 30 pounds per annum, after which it was increased to 40. In addition came fees for weddings, funerals and christenings as well as payments for extraordinary services. There was also the benefit of long holidays: services were not sung between the ends of June and September, during the week following major feasts or when the Court was away from its main houses of Hampton Court, Windsor Castle, Greenwich, Richmond or Whitehall. Ferial services were sung with just half the choir (sixteen men and twelve boys), with Gentlemen bound to appear only on alternate months. This provided the men with a total of 100 or more free days per year.

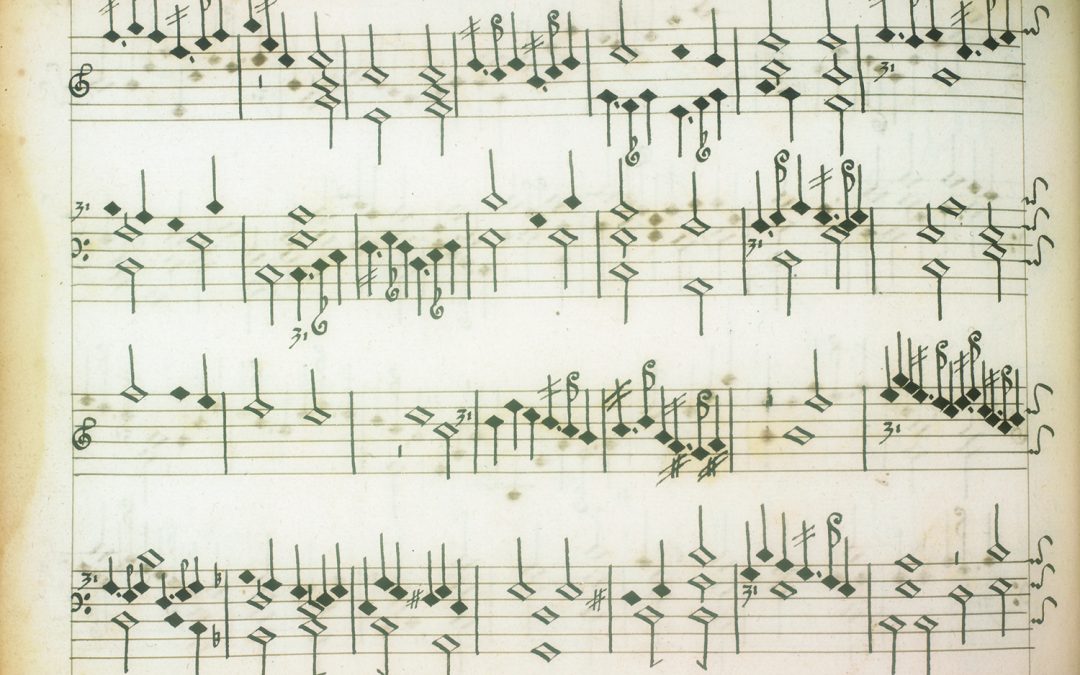

Fig. 01: John Baldwin’s distinctive manuscript style. LNB: fol. 126v. (Photo: The British Library.

As Alan Brown (3/1999, 199–200) points out with regard to the calligraphy (hereafter referred to as the Nevell hand), this is ‘the most beautifully written of all virginal manuscripts’. Rather than round noteheads with stems emanating from their sides, Baldwin uses rhomboid lozenges with thicker strokes for their lower left and upper right diagonals. Stave paraphernalia is equally stylised, and the uniformity of the notation suggests that copying occurred in a relatively short timeframe. Only one other such source of keyboard music demonstrates a similar aesthetic appeal and attempts at uniformity, Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (hereafter FVB), which was very likely copied by Francis Tregian while serving a sentence in the Fleet Prison for debt.9 Therefore, it is desirable to see what motivated Baldwin to cultivate such a unique calligraphy. Four other Baldwin sources have survived. They are:

- GB-OC, MSS Mus. 984–988 (hereafter, Ch1): a set of partbooks of Latin motets and English anthems, consort music and consort songs.10 The majority of the manuscript is in the hand of their owner, Robert Dow, a fellow at All Souls College, Oxford, whose legend ‘Sum Roberti Dowi’ is inscribed on each book’s title page, and it is thought this occurred in the 1580s. Dow’s manuscript style is not unlike the Nevell hand, with clearly defined lozenge noteheads with stems emanating from their apexes. According to the Christ Church Library catalogue, Baldwin acquired the books after Dow died in 1588.11 It was probably after this that Baldwin copied two Latin motets on to several blank pages that divided the Latin and English material. The motets in question are Robert Parsons’s O bone Jesu and Nathaniel Giles’s Vestigia mea.12 It might be that Baldwin developed his calligraphy to emulate Dow in order to maintain consistency in the notation’s appearance.

- GB-Ob, Mus. Sch. e. 376–381 (Forrest-Heyther Partbooks): according to the Bodleian Library catalogue, Baldwin acquired the manuscripts c. 1581 and they remained in his possession until he died in 1615. The first part of each is in the hand of the poet-musician and priest, William Forrest. Baldwin completed the Agnus Dei of Taverner’s Missa O Michael in the sextus book and added three further masses to the same part in the Neville hand13Again, Forrest’s contribution is stylised, though not as clearly defined, and the point where Baldwin’s completion begins is easily perceptible.

- GB-LBl, M.24.d.2 (Baldwin Commonplace Book): during Baldwin’s lifetime, commonplace books were fashionable and used to conserve anything that was of particular interest to their owners. Baldwin’s contains Latin motets, anthems, services and madrigals, along with 20 of his compositions, and theoretical exercises.14 The majority of its calligraphy is unremarkable, though the piece occupying the verso side of its last folio, Wilkinson’s canonic motet Jhesus autem transiens, also uses the Nevell hand. It bears the date 1594. Notably, the manuscript also contains two poems to music, one of which is almost entirely dedicated to William Byrd.

- GB-Och, MSS 979–983 (hereafter Ch2.): a set of part-books in Baldwin’s hand throughout, similar to most of the Commonplace Book.

Considering the contributions Baldwin made to both Ch1 and Ch2 and the other material they contain, it becomes apparent that nothing is remarkable about his style apart from its neatness and precision. By dissecting the musical and written texts of concordances found in Ch1, Ch2 and the Commonplace Book, Hilary Gaskin (1985, 160) demonstrates that the earliest of the three is Ch1. If so, then most of the notation in the commonplace book and Ch2 was written in a manuscript style that was Baldwin’s standard.

We do not know if the completion of Forrest-Heyther or the additions Ch1 led to Baldwin developing his Nevell hand. Gaskin suggests two possibilities: that he selected a style from a ‘repertoire’ of scribal hands to match their sources closely; or that he developed the style for one of the two projects by modelling it on the existing notation. A third possibility remains, though. A glance at such surviving partbooks as GB-Lbl, Add. MS. 15166 or GB-Cu, Dd.13.27 suggests the style of the earlier sections of Forrest-Heyther or Ch1 was more common than not. Indeed, the use of lozenge-shaped noteheads might well be the sort of anachronism that marks a transition from the puncta of graduals and antiphonaries to the type of notation that was to become common during the seventeenth century. From this perspective alone, we might assume that this ‘ecclesiastical style’ was the source of the Nevell hand: it was a style with which Baldwin was no doubt familiar and possibly the one he used when receiving payments for copying for St George’s Chapel.

iv. The Byrd connexion

Much has been said of Byrd’s involvement in the selection and ordering of pieces in LNB. According to several commentators, he organised the collection and was responsible for its corrections, yet a thorough examination of the book suggests otherwise. The first problems arise from the manuscript’s structure. Contrary to some descriptions, it does not fall into two distinct sections by design (Harley (2007, 1) and Popović (2019, 153) prefer three). It is easy to see how this conclusion came about: the book begins suitably with two pieces named for Nevell, her ‘grownde’ and ‘qui passe: for my ladye nevell’, and a central collection of pavans and galliards. They are followed by Nevell’s ‘voluntarie’ (LNB 26), which has been taken as the beginning of the next section.15 Harley suggests the order of pieces reflects Byrd’s methodical mind, citing the centrally placed dances, which appear to form a discrete unit. Popović (2019, 147–162) goes one step further by dissecting familial connexions between the Nevells and those pieces that bear others’ names. He discusses links between heraldry and humanism and the positioning of pieces within the book as a whole. We must be cautious about both their conclusions, not least because no overall reason behind the running order is apparent.

Except for the ‘tennthe’ pavan and galliard pair, the dance portion (LNB 10–25) forms a discrete unit within the manuscript. When examined closely, it becomes apparent that the first five were organised by design. As Harley points out, their tonalities alternate between major and minor modes, and a metrical order in which their respective pavans vary between strains of sixteen and eight semibreves might indicate that they were composed as a ‘suite’. Whether or not the sixth pavan-galliard pair caps the sequence needs some discussion. Its Ionian mode certainly follows the precedence set out in the series, but the pavan is 96 semibreves long and, if it belongs, should be 48. It has several characteristics that set it apart from the earlier dances, which tend towards passages of homophony that are intermittently linked by brief divisional flourishes and an occasional point of imitation. By comparison, a carefully organised imitative plan suggests the sixth pair to be a more mature composition. It is also set apart from the earlier dances since it is the first to bear a name, Kinborough Good, daughter to Doctor James Good and probably a Byrd pupil (Moroney, 1999, 92). Therefore, it seems that rather than ending the sequence of five dances, it marks the beginning of one that is more disparate: two have no galliard, and the grand ‘passinge mesurs’ needs little discussion concerning its place as the final pair of the group. Given that Byrd limits his keys in LNB to just four types (finalis on C, D, G and A), it is probably by coincidence that the sixth is in the Ionian mode. Indeed, it is quite possible that since the first pavan is known as a five-part consort work (D-Kl 4o MS Mus 125), some of the nine dances that follow also may have existed in similarly scored versions that have not survived the years.16

There remains the question of why the tenth pavan and galliard (LNB 39–40) appear so late in the manuscript. Harley suggests they were composed as the book was being compiled, but we may discount his thesis: the dances were named for William Petre, son of Byrd’s patron, John. Petre was born in 1575 and 16 years old at the time LNB was compiled. Byrd appears to have had a close relationship with the family: he was a frequent visitor to their house at Ingatestone during the 1580s (Kerman, 2/2001, 720; Knights, 2019). There are few reasons to doubt that William Petre had been an occasional Byrd pupil during these years since his father’s interest in music and patronage of the composer would have assured the boy received a thorough musical training. That the dances carry his name might indicate they were written with a didactic intention, a conjecture highlighted by the fingering they contain, which is of the type that would have been useful to less experienced players. If so, it may allow us to place a date of composition before 1588, when Petre began studies at Oxford at the age of thirteen Hasler (1981). That the dances are so placed probably has a more straightforward explanation: they were simply overlooked or were not to hand when LNB was compiled.

In total, Baldwin added or included the fingering in eighteen pieces. Apart from the tenth pavan and galliard, most is occasional and implies that some of Baldwin’s sources once served a pedagogical role.17 Whether or not it was added for Lady Nevell’s benefit cannot be said. However, apart from a few later clarifying marks and barlines (possibly the work of Burney or Hawkins) and some corrections, the book seems not to have been used at any point for performance. Indeed, its remarkable condition and lack of the usual signs of wear imply it remained mostly untouched. Some of the fingering is problematic since a portion of it is wayward. LNB 1, for example, contains four instances where wrong numbers are suspected, and elsewhere, left-hand finger designations appear to be inverted. Such erratic and contradictory fingering has little practical value and would not have emanated from an experienced musician, let alone a keyboard composer of Byrd’s stature. 18However, viewing these minor errors in light of other more egregious problems necessitates the scrutiny of Alan Brown’s suggestion that Baldwin must have had access to Byrd’s holographs (3/1999, 199–200).

These errors include a missing bar in LNB 25, ‘the galliarde to the passinge mesurs: pavian of Mr W Birdes’ and a missing note and wrong rhythm in the first bar of LNB 38, ‘munsers almain’. While we might pass the latter off as a simple clerical inaccuracy, the same rhythmical error occurs in other parts in bars 2 and 4, suggesting they were present in Baldwin’s source and this diminishes its authority considerably. Indeed, the same rhythm in FVB, which is generally thought to contain less reliable texts, is correct and suggests a source that was closer to Byrd.

Other amendments require a little examination. Most are exceptional since they are not in Baldwin’s hand. Margaret Glyn (2/1934, 38–9) was the first to propose that Byrd corrected the manuscript and, since her thesis has found favour with others, it deserves some scrutiny. Emendations may be grouped into two categories:

- Immediate corrections made during the copying process. Ink pigmentation and calligraphic style indicate that these emanated from Baldwin and include the addition of missing notes (e.g. LNB 10, ‘the firste pavian’, bar 18), clarifications of ambiguities (e.g. LNB 18, ‘the fifte pavian’, bar 33), the deletion of erroneous notes or accidentals (e.g. LNB 31, ‘have with yow to walsingame’, bar 117) and the addition of bar 59 at the end of LNB 32, ‘all in a garden grine’, which Baldwin erroneously passed over but pointed out with: ‘here is a falte, a pointe left out, wh ye shall find prickte, after the end of the nexte songe, upon the . 148 . leafe : –’.

- Later emendations in two or more hands suggest several layers of correction. They may be subcategorised as:

- The addition of ornaments and accidentals: ink pigmentation and style suggest they were made by the same person (here called scribe B). These occur throughout the manuscript.

- The addition of clefs, the correction of wrong notes, further accidentals and ornaments, and the addressing of lacunae: these are not Baldwin’s work since the approach taken is shoddy. Noteheads might be elongated when the original is corrected to an adjacent space or line (e.g. LNB 37, ‘sellingers rownde’, bar 171), or where void noteheads are filled to make them half their length (e.g. LNB 8, ‘the hunts upp’, 163, R2). There are also instances where some corrections are wrong (e.g. LNB 9, ‘ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la’, 136.6/6, L1) and one where the wrong clef has been added (LNB 33, ‘lord willobies welcome home’, 44R). These all appear to be in the same hand (scribe C).

- The addition of complete beams as ties (Baldwin used short, angled limbs): occurrences are found mainly in the first pieces and become infrequently used as the book progresses, suggesting a cursory correction occurred. It is difficult to ascertain if scribe C was responsible for these. However, this scribe was not responsible for:

- The inclusion of conventional curved lines as ties: these are more frequent and applied throughout the manuscript. Because of ink pigmentation, we must assume the copyist was not responsible for either category 2b or 2c, which demonstrates the presence of another hand (scribe D).

- The addition of barlines and strain/variation numbers: Baldwin did not demarcate strains in LNB or add numbers to either the strains of dances or variations of grounds and fantasies. Occasionally, barlines were added to clarify metrical subdivisions (e.g. LNB 8, ‘the hunts upp’, 136). These might be the work of scribe B.

- Other corrections: there are two instances where clarification marks were added in pencil. Although mentioned in this book’s commentary, it is probable that these are from a much later date and have little bearing on this overview.

Since 2a is restricted to ornaments and accidentals alone, matching Baldwin’s calligraphy would have been of little importance. They are mostly unobtrusive and noticeable only because ink pigmentation is different or spatial positioning does not correlate with Baldwin’s thoroughly consistent approach. Yet no other corrections attempt to match his style. Many are crossings or scribblings out (e.g. LNB 35, ‘hughe ashtons grownde’, 110.7) and others include the addition of lines and beams as ties. While most are accurate, none meets the standard associated with the copyist. Therefore, we must assume that Baldwin was not available when the corrections of scribes C and D were undertaken. Indeed, we might conjecture that their corrections’ wayward appearance is work of a considerably later period, perhaps when the book had lost its immediate intrinsic value.

Baldwin was an accurate copyist, and the addition of the missing bar at the end of ‘all in a garden grine’ suggests that he revised his work. It is surprising, therefore, that scribe B had to add so many ornaments after the copying was complete. A few might be omissions on Baldwin’s part; of 242 revisions, there are over 120 added ornaments. It could be that Byrd was scribe B and that the ornaments were afterthoughts. However, it is doubtful that he would think to ornament to the ninth pavan (LNB 25) or ‘munsurs almaine’ (LNB 38) but overlook their glaring errors. The quality of Baldwin’s sources are therefore sometimes questionable, and their respective mistakes suggest copies that were some way removed from the holographs.

The proposal that Byrd oversaw the compilation of LNB ties up many loose ends concerning its copying too conveniently. His participation in the process is here questioned since it is, at best, conjecture and enough evidence exists to doubt the notion that Baldwin prepared the manuscript from holographs and, for that matter, that Byrd was involved in its correction at even the most fundamental level.19

With Byrd relegated to the margins of that picture, we are left wondering who or what provided the impetus for LNB. Byrd, himself, cannot be discounted on this front since he probably knew the Nevells from both Court and through his patrons, one of whom, Sir William Petre, was related to Sir Henry (Popović, 2019, 154). It would not be out of character for Byrd to have ingratiated himself with the Nevells to court their patronage. Yet commissioning such a lavish present as this would have been an extravagant move, even for Byrd, and we know of no other instances where he made a similar gesture. Indeed, were he behind the commission, he would have provided Baldwin with any manuscripts he had, and would have ensured they were in good order. This did not happen. Sir Henry or Lady Nevell are also contenders: their connexions with Windsor have been established, and Baldwin had, before 1591, been paid for copying music at St George’s Chapel, of which the Nevells might well have been aware. Byrd might have been involved in suggesting repertoire. However, judging from Baldwin’s other activities in this area, we might assume that he was a collector of the music of composers he admired and that he copied music for his own purposes. The completed partbooks and commonplace book demonstrate this interest; while their contents and purpose have already been discussed, an aspect to the latter requires deeper scrutiny. Of the 201 works that Baldwin meticulously copied, the larger proportion (32 in number) is devoted to Byrd. In addition, a poem in Alexandrine couplets, suitably composed on 25 July 1591, laurels both its domestic and ‘strainger’ composers.20 The first portion takes up half its 60 lines, after which Baldwin reserves the remainder for one man alone:

an englishe man, by name: willm birde for his skill:

Wc I should have sett first: for soe it was my will:

whose greate skill and knowledge: doth excelle all at this tyme:

and farre to strange countries: abroad his skill dothe shyne:

famus men be abroade: and skilfull in the arte:

I do confess the same: and will not from it starte:

but in ewropp is none: like to our englishe man:

we doth so far exceede: as trulie I it scan:

as ye can not finde out: his equale in all thinges

throwghe out the world so wide and so his fame now ringes:

With fingers and with penne: he hath not now his peere:

for in this world so wide: is none can him come neere:

the rarest man hee is: in musicks worthye art:

that now on earthe doth live: I speake it from my harte:

or heere to forth hathe beene: or after him shall come:

none such I feare shall rise: that may be calde his sonne:

O famus man of skill and iudgement greate profounde:

lette heaven and earth ringe out: thy worthye praise to sownde:

nay lett thy skill its selfe: thy worthie fame recorde:

to all posteritie: thy due deserte afforde:

and lett them all which heere: of thy greate skill then saie:

fare well fare well thou prince: of music now and aye:

Fare well I saie fare well: fare well and heere I end:

fare well melodious bird: fare well sweet musicks frende:

all these things do I speke: not for rewarde or bribe:

nor yet to flatter him: or sett him up in pride:

nor for affeccion: or owght might move there towe:

but even the truth reporte: and that make known to yowe:

Loe heere I end farewell: commintinge all to god:

who kepe us in his grace: and shilde us from his rodd.21

This section clarifies Baldwin’s awe of the composer, whom he calls ‘homo memorabilis’ (which would perhaps be an unusual description of someone actually known to him).22 Therefore, it is something of a mystery that Baldwin has been kept much in the background when dealing with LNB, his role relegated to one of copyist. It is not unreasonable, though, to think that he collected more than the pages of the commonplace book reveal and that among these were Byrd’s keyboard compositions. If so, they might well have formed the sources of the music he copied in LNB, which might also explain why other sources are sometimes more reliable. Since Sir Henry was an influential figure in Parliament and at Court, Baldwin’s motivation might have been something as simple as personal advancement, perhaps coming in the form of a right word from the right man to the Dean of the Chapel Royal.

• • • •

Bibliography

Andrew Ashbee and John Harley, The Cheque Books of the Chapel Royal, Vol. 1 (Aldershot, 2000).

Jon Baxendale and Francis Knights (eds.) The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (Tynset, 2020).

Ernest Brennecke, ‘A Singing-Man of Windsor’, Music and Letters, 33 (1952), 33–40.

Alan Brown (ed.), William Byrd, Keyboard Music: I, Musica Britannica XXVII (London, 3/1999).

Hilary L. Gaskin, Music copyists in late sixteenth-century England, with particular reference to the manuscripts of John Baldwin (PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 1985).

Margaret H. Glyn, ‘The National School of Virginal Music in Elizabethan Times’, Proceedings of the Musical Association 43rd session (1916–1917), 29–49.

P. W. Hasler (ed.), ‘Neville, Sir Henry I (d.1593), of Billingbear, Berks’, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558–1603 (London, 1981).

John Harley and William Kinderman, ‘’My Ladye Nevell’ Revealed’, Music & Letters, Vol. 88, No. 1 (Feb. 2007), 193–194.

P. W. Hasler (ed.), ‘Neville, Sir Henry I (d.1593), of Billingbear, Berks’, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1558–1603 (London, 1981).

Joseph Kerman, ‘William Byrd’, New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie, Vol 4, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 714–723.

John Milsom (ed.), The Dow Partbooks: Oxford, Christ Church Mus. 984–988 (Oxford, 2010).

Moroney, ‘Bounds and Compasses: The Range of Byrd’s Keyboards’, in Banks, Searle and Turner 1993, 67–88.

Oliver Neighbour, The Consort and Keyboard Music of William Byrd (London, 1978).

Tihomir Popović, ‘Hunting, Heraldry and Humanists: Reflections of Aristocratic Culture in My Ladye Nevells Booke’ in Smith (2019).

Richard Rastall, The Notation of Western Music: An Introduction (London, 1983).

Liam Sims, ‘A binding from the library of John Bull at Cambridge University Library’, National Early Music Association Newsletter iii/1 (Spring 2019), 62–65.

David J. Smith, ‘Making Connections: William Byrd, “Virtual” Networks and the English Keyboard Dance’, in Woolley and Kitchen (2013), 19–30.

______ (ed.), Aspects of Early English Keyboard Music before c.1630 (Abingdon, 2019).

Alison Margaret Welch, The Baldwin Part Books and a Case Study of the Eight Settings of the Respond Dum Transisset Sabbatum (Master’s thesis, University of Birmingham, 2017).

- ‘Neville, Sir Henry I’ in Hasler (1981).

- According to Neighbour (2012), both Bergavenny and Abergavenny were in use in the seventeenth century.

- Woolley (2006).

- GB-Lbl, Add MS 1591.

- The binding is very similar to that of a music book owned by John Bull. See Sims (2019, 62–65).

- The number 16 and the initials N M W is a possible suggestion.

- Variously spelled Baldwin, Baldwine, Baldwinne, Baldwyn, Baudewyn and Bawdwine.

- According to the St George’s rolls, Baldwin earned £12 / 2 / 0 d in 1586, £13 / 4 / 1⁄4 d annually between 1591 and 1593.

- Baxendale and Knights (2020).

- For a facsimile edition, see Milsom (2010).

- Library catalogues may be accessed online through their institutions’ respective websites.

- These are masses by John Sheppard, Christopher Tye and Richard Alwood.

- These are masses by John Sheppard, Christopher Tye and Richard Alwood.

- GB-LBl, R.M.24.d.2.

- ‘a fancie’ (LNB 2 and 36), although for the latter, her name was appended only to its title in the index in a later hand that attempts to match Baldwin’s calligraphy.

- See Rastall (1998).

- These are: LNB 1– 7, 10, 12, 23–27, 34, 36 and 39–40.

- Baldwin has not corrected any fingering errors and this suggests he was not a keyboard player himself.

- Popović, 2019, comes to the same conclusion.

- The poem was written on the book’s last flyleaf.

- GB-LBl, R.M.24.d.2, end of manuscript, lines 31–60.

- It is intriguing that the only recorded encounter between the two men was at the coronation of James I in 1603, at which they both sang (Ashbee and Harley, 2000, 186). After Baldwin entered the Chapel Royal, it should be accepted that he came into more familiar contact with the composer.