By Jon Baxendale

This article first appeared in Early Music Performer No. 45, November, 2919.

Nicolas de Grigny’s Premier livre d’orgue was engraved at the atelier of Claude Roussel, who flourished between 1682 and 1725 and whose premises were situated on ‘rüe St. Jacques au dessus des Mathurins’.1 Only two surviving examples of the publication are known: a single copy of the original imprint of 1699 and a second impression made under the auspices of Christophe Ballard in 1711. Although the later edition used Roussel’s engravings, a number of corrections to the music are noticeable.2 The book is in oblong quarto format and contains a title-page, the legally required Extrait du privilège du Roy (this was probably removed before the 1699 imprint was bound), an index and 68 pages of music. In total, this amounts to 72 pages contained in nine gatherings.3

The title-page of the 1699 impression announces that the music was available from Pierre Augustin le Mercier – a bookseller and printer, who was to be found ‘à l’entrée de la rüe du Foin du côté de la rüe St Jaques’ on Paris’s Left Bank – and from the composer in Reims. The publication was likely financed by Grigny himself. Unlike other music engravers such as Henry de Baussin, who was regularly employed by Christophe Ballard, Roussel’s work was not restricted to the production of music alone and, according to the online catalogue of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, he was active as a stamp and mapmaker.4

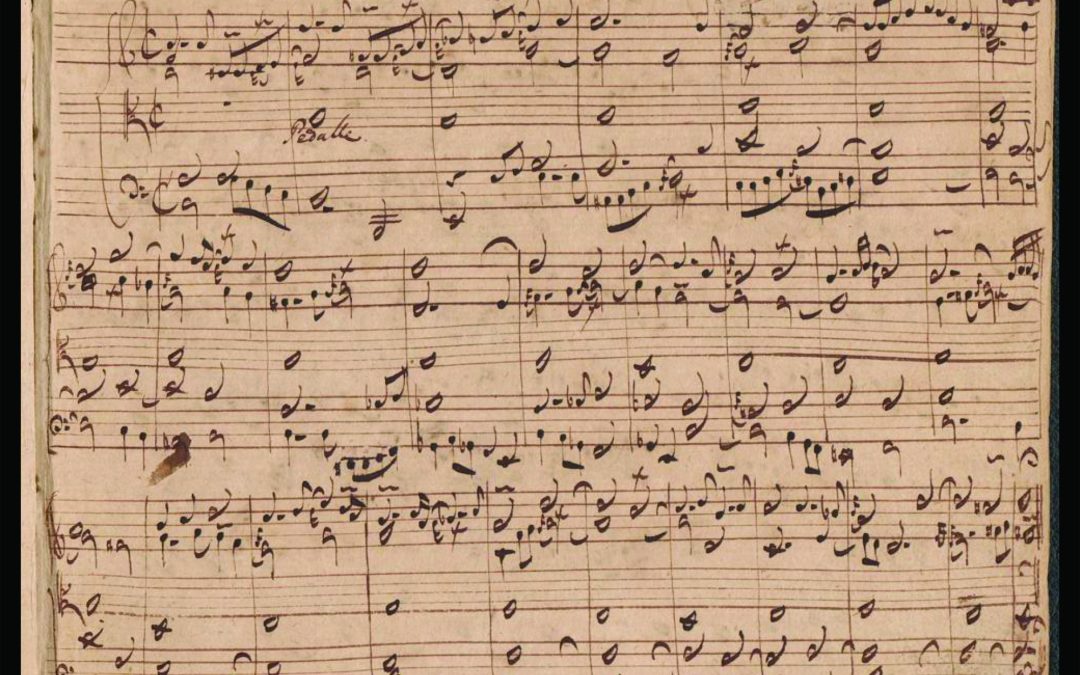

Fig, 01: Roussel’s engraving of Grigny’s first Kyrie, issued by Christophe Ballard in 1711.

Publishing music came at a high cost, since it involved not only engraving and printing but securing authorial rights. Known as a Privilège du Roy, rights had been a legal requirement since the early 1500s for all material that was disseminated publicly, and although they provided authors and composers with a form of copyright within the kingdom, they were also a means by which the state could censor seditious material and generate income for its coffers. No records are known to exist concerning the cost of a privilege in 1699, but we do know that, by the middle of the eighteenth century, the price for the printing of up to 1500 impressions of books in oblong quarto format was as high as 120 livres.5 In addition were Roussel’s fees. These appear to have been exceptionally high, as evinced in a contract dated 6 October 1720 between Roussel and the composer Thomas Louis Bourgeois for the engraving of his first book of cantatas. It stipulates a sum of ‘4 livres 10 sols par planche’ and there is every reason to think that similarly high fees would have been applied in 1699.6

Research by Laurent Guillo has uncovered the printing costs at Ballard’s workshop. Excluding the paper, the price for two formes (printed sheets) of engraved music ranged from approximately 12 sols for large print runs, to 29 sols for shorter ones. Thus, it can be expected that, for Grigny, printing 20 copies would have been roughly 35 livres excluding paper. If a conservative estimation of 60 livres for securing the privilege and Roussel’s fee of 290 livres is applied, the total cost for the first 20 prints of Premier livre d’orgue would have been in the region of 385 livres.7 If one considers that Grigny’s stipend at Saint-Denis was 200 livres annually, it is easy to see that such ventures constituted a considerable investment.8

These costs ensured that most composers’ print runs were limited to small numbers. Unlike typeset publications, engraved plates had limited lifespans and although the durability of copper made it the preferred medium for printing books, tin sheets were generally used for music which might not always have been expected to run to a second impression. Despite its being inexpensive, though, tin was good for only up to around 200 copies and this resulted in small batches of only 10 to 20 volumes being printed at any one time.9 It is unlikely that the initial batch of Premier livre d’orgue would have been any different and how it was received is not known. There was, though, enough life remaining in the plates to facilitate Ballard’s 1711 edition.

It cannot be said what prompted a new edition. Although the attraction of the music might have been a factor, it is unlikely that this was enough for Ballard. More probable is that despite the publication of a considerable number of organ books in the last half of the seventeenth century, most of those that were printed in short runs would have been unavailable by the turn of the eighteenth. In comparison, the first decade of the 1700s saw only a handful of organ publications, most of which were meagre and none of which was published by Ballard.10 It is possible that this dearth of available material acted as a catalyst: always the businessman, Ballard would have sought every opportunity to capitalise on an underprovided market, and the existence of the original plates must also have been a deciding factor.11 These would have been bought from Grigny’s widow. We know little of her husband’s financial circumstances (such details of his life have yet to emerge), but the prospect of deriving income from this sale must have been attractive: engraved plates were valuable assets that were often bequeathed to relatives or friends. For lesser composers, values were estimated at the market price of the metal. For example, the inventaire après décès of Laurent Gervais, who died in 1748, appraised the plates of his cantata Le Printemps at a mere 18 sols per livre-poid. However, the beneficiaries of popular composers were more fortunate: the division of Jean Henri D’Anglebert’s estate in November 1691 estimated the value of the 136 plates of his Pièces de clavecin at 1600 livres.12 Into which category Grigny fell cannot be said. While he must have earned some notoriety in Paris, his sojourn there was nonetheless short enough for him to have been largely forgotten by the time of the Ballard impression.13

Roussel’s engraving is typical of his workshop in its appearance. It is generally clear and, at times, elegant. Staves are scored according to the format of each movement, with eight-stave pages reserved for manualiter pieces and nine for those with pedals. Music begins on the verso side of a folio, often negating the need for page turns and where the end of one piece and the beginning of another share same stave to save space, redundant stave-lines between the two were flattened out to avoid confusing the player.14

It is clear that a degree of parsimony was required on the part of the engraver. Prefatory material and music are contained exactly within nine gatherings with no room for error and although this sometimes produces a cramped look, it demonstrates that some thought had gone into how much space would be needed before work began.

Such planning was integral to the engraver’s craft: the number of notes would have been counted to determine how many bars would go into a system and how many of these a page could accommodate. He would also work through the music, deciding where line breaks would occur and what room was necessary for leger lines and titles. This would have been a relatively easy process for simpler pieces such as the duos and trios, but the complexity of slower movements, such as Grigny’s intricate récits, would have posed a challenge.

Although notarised contracts such as the one between Roussel and Bourgeois stipulated that payment would be met only after everything had been properly engraved and corrected, the composer nevertheless had an obligation to provide an accurate copy of the music.15 When considering these clear and complementary responsibilities, it is important to question why Grigny’s publication was so crudely executed. Few pages are mistake-free and while most errors are inconsequential, such as the omission of anticipatory slurs or augmentation dots where the composer’s intentions are evident, more serious problems are apparent. Ornaments, leger lines and ties are omitted, and there is a considerable number of wrong notes. More egregiously, Roussel appears to have engraved the fourth, fifth and sixth Gloria versets in the wrong order, giving the verse ‘Qui tollis peccata mundi’ the grand jeu Dialogue and not the nuanced Recit de tierce en taille it deserves. A number of corrections are evident in both imprints, which are visible as re-rastered staves or oversized noteheads, but most are so inexpertly undertaken that we must assume that Roussel was far from the experienced music engraver he wished his clients to believe.

These inaccuracies are intriguing. Examples of Roussel’s surviving music date only as far back as the year Grigny’s commission was undertaken, and it is likely that his activities before then were restricted to making maps and stamps. Apart from the Grigny livre, we know of two other scores he prepared in 1699: an anonymous book of trios which he released under his own auspices and Louis Marchand’s Pièces de clavecin: livre premier.16 A comparison of the engraving styles makes it possible to place these three books in chronological order. The trios came first and demonstrate all the crudities expected of a fledgling music engraver: noteheads are punched inexpertly, their spatial positioning is judged poorly, and such conventions as those governing stem directions are ignored. The Marchand book fared little better, and although it has a more appealing appearance, it is nevertheless inaccurate and poorly executed. By the time Grigny’s book was published, however, Roussel’s style had evolved: noteheads, beams and flags are now handengraved; and an attention to the visual appearance of a page is evident. This was to remain his style for the remainder of his career.

Yet when comparing these publications with Louis-Nicolas Clérambault’s Premier livre de pièces de claveçin, which Roussel engraved in 1702 and augmented two years later with additional material, a marked difference is noticeable since Clérambault’s book is substantially more accurate.17 Apart from a few misplaced, stray or redundant rubrics and accidentals, the work is of a considerably higher calibre, easy to read, and pays close attention to such details as the placement of ornaments, petites notes and slurs. Thus, we see in Roussel an engraver capable of professional work, even though the faults demonstrated in the trios of 1699 indicate that, unlike the musician-engravers that emerged after the 1660s, Roussel had limited musical knowledge. This means that he would not have been in a position to make decisions on behalf of the composer, which would have led to problems interpreting the information the manuscript contained. Instead, he would have relied on his skills as a draughtsman of some repute, and this led him to reproduce exactly what he saw. This is demonstrated when comparing the positioning of ornaments in the three volumes. In Marchand and Clérambault’s books, for example, pincés are placed over or below notes whereas in Grigny’s they are usually placed diagonally to the left of noteheads, even when they are partially obscured by the stave. We must assume, therefore, that their positioning was Grigny’s preference and that the score reflects his rather than the engraver’s notational idiosyncrasies.

The inaccuracies of the Marchand publication demonstrate this more clearly. Two autograph manuscripts of his organ music, which are now housed in the Bibliothèque municipale de Versailles, provide us with an idea of the problems that music engravers must have often encountered.18 It contains complete pieces and sketches, some of which demonstrate a copybook style and others that appear as if they were composed at a keyboard. None would have been acceptable as a fair copy by graveurs de musique and while it is likely that the pieces were written for Marchand’s own use, it is highly probable that the score he presented to Roussel when preparing his first harpsichord book for publication was similar in appearance.

It might be that Grigny gave Roussel a manuscript of the same calibre. If so, the problem would have been compounded by his residency in Reims. Some 150 kilometres by road from Paris, a journey to the capital would have taken three days – a difficult undertaking for the organist of an important provincial cathedral.19 There is every likelihood, therefore, that after signing the contract with Roussel, Grigny’s involvement was minimal, perhaps non-existent. This would have also meant that Roussel had little guidance as work on the preparation of the plates and their proofing was undertaken. As a control, it is necessary to return again to Clérambault’s Pièces de claveçin and question why it is the most accurate of the publications discussed here. A feature of Clérambault’s style as a composer is the attention paid to such details as ornaments, their placing and their appearance, as demonstrated in his two préludes non mesurés where pre- and on-beat ports de voix are distinguished through a set of vertical lines marking their temporal positions as the music progresses. It is important to note, though, that Clérambault lived close to Roussel’s atelier on rue Saint-Jacques and his choice of engraver was probably made because of this proximity. It would have facilitated cooperation between the composer and Roussel and there can be few doubts that Clérambault took every chance to oversee the preparation of his first publication.

History has been unkind to Roussel, especially where the Grigny book is concerned. Yet it would be wrong to think that Grigny’s work suffered at the hands of its engraver. Rather, we might view its deficiencies as the result of the fair copy’s inadequacies and a probable lack of communication between composer and engraver. Indeed, we might be grateful to Roussel since Grigny’s Premier livre d’orgue was to come into the hands of J. S. Bach and J. G. Walther, and their versions provide a unique insight into a foreign interpretation of the French style.

The J. S. Bach and J. G. Walter copies

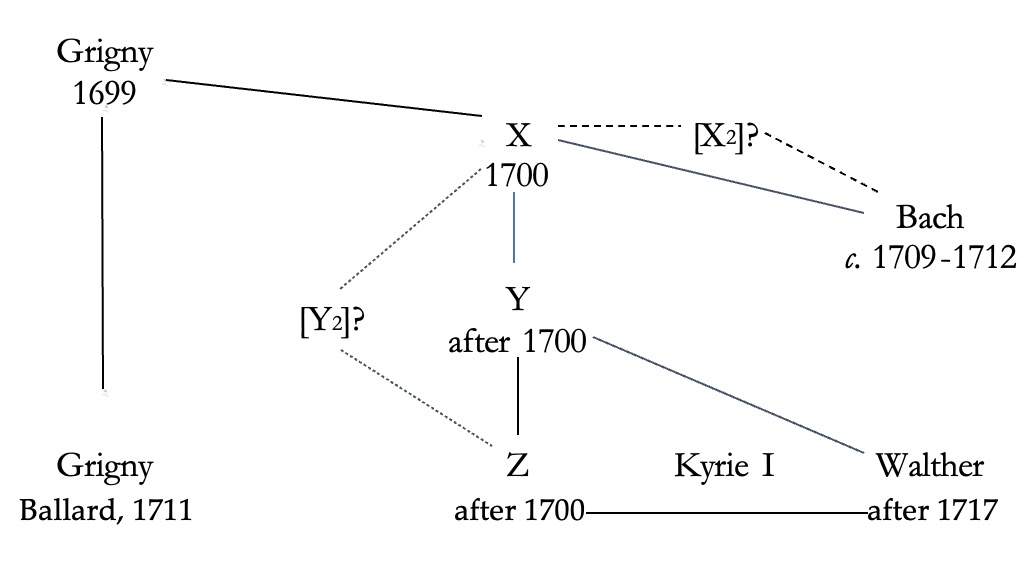

While a number of modern editions are commercially available, none presents Grigny’s 1699 imprint without deferring to Bach and Walther.20 Some of their emendations might be of significance from a musicological perspective, though the majority address such inconsequentialities as the addition of ties and anticipatory slurs from petites notes, and ornament placing where the engraving is at fault. Nothing is known of their Vorlage, yet there is enough reason to suggest that it was German and that one was not copied from the other. Bach’s and Walther’s copies both rationalise the system of short-stemmed notation found in the original, which suggests this change was present in a common source or sources derived from it. This notation was an elegant means of keeping the stems of dense chords from clustering but is quintessentially French and rarely found in German sources. The harpègements glissés in bars 58 and 59 of Dialogue à 2 Tailles de Cromorne et 2 deßus de Cornet p.r la Cõmunion similarly suggest they were not working directly from the print. This is common to both the German sources, but each contains the same misinterpretation in that the petites notes and their parents have been re-aligned vertically. None of these are features that a French copyist would have misunderstood or thought to emend.

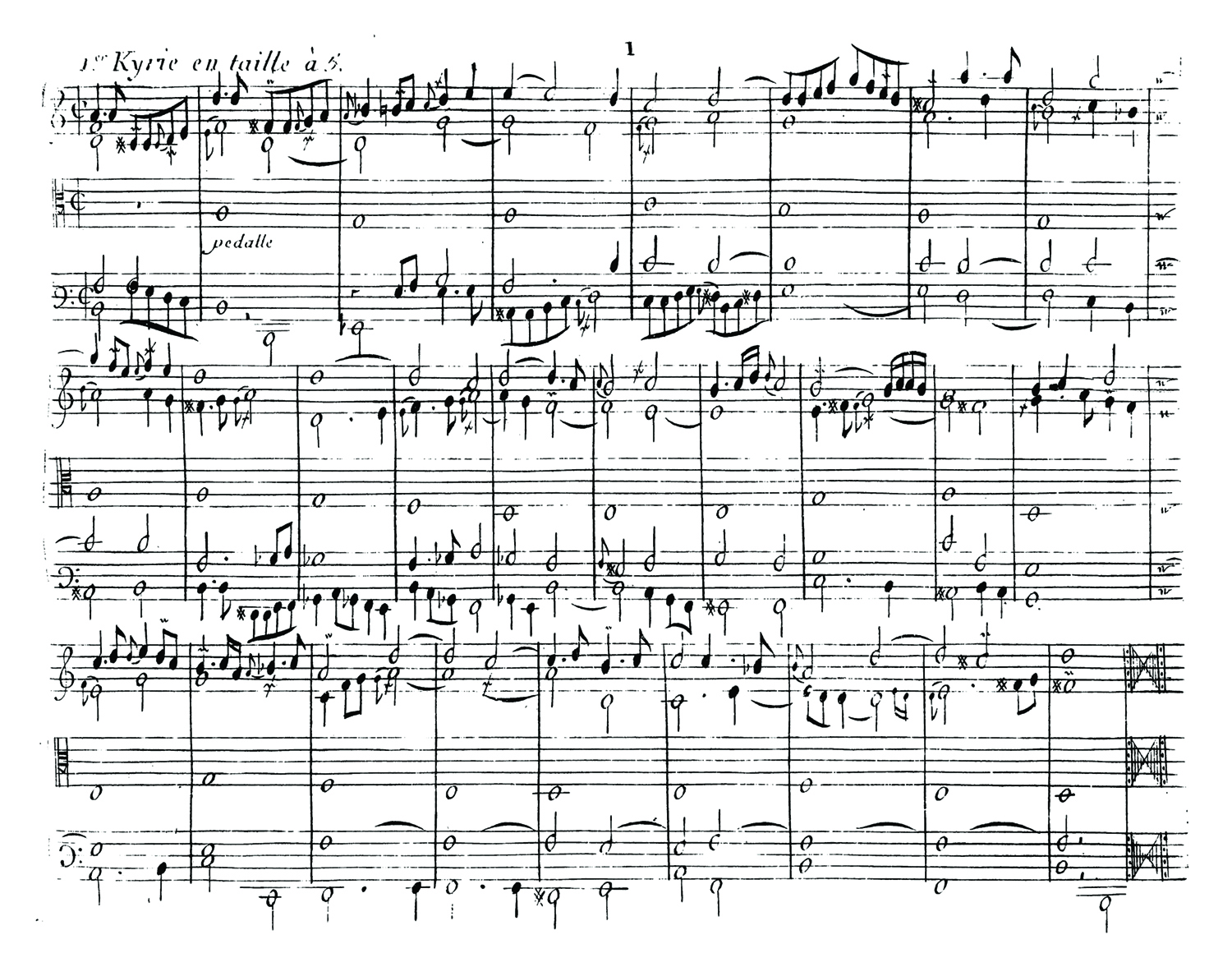

Fig. 02: Bach’s copy of Grigny’s first Kyrie

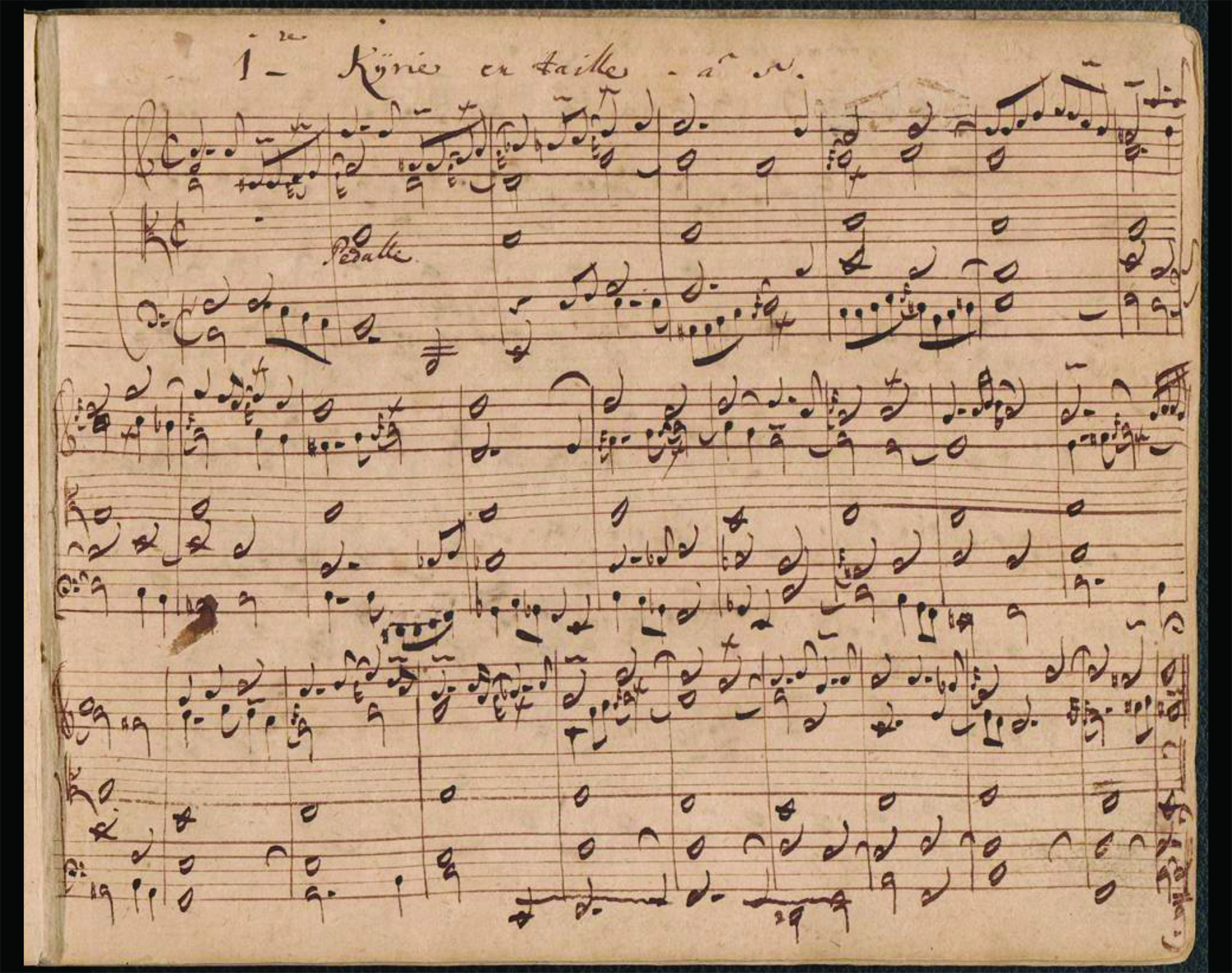

Both the Bach and Walther copies report the edition was from 1700, which has led to speculation that they were made from a now-lost imprint of that year.21 This is improbable. The date engraved would have had to match that of the privilège, which was finite. Unless Grigny had secured a blanket license to cover all compositions covering a specified period, any alteration would have required applying for his credentials afresh.22 It is more likely that the date Walther and Bach’s versions bear was that of their hypearchetype. Karin Beisswenger suggests that the manuscripts were produced independently: handwriting and watermark analysis of Bach’s copy has led her to conclude that it was made over an extended period between c. 1709 and 1712.23 She indicates that Walther’s copy was made after Bach left Weimar in 1717. Walther omitted the first three versets, leaving five blank pages which he approximated would be the space they required. At a later point, a different hand began entering the first Kyrie, which stops after seven complete and two incomplete bars.

Of the two, Bach’s version contains fewer changes to the original version. Both have variants in common that are not in the original, yet Walther’s copy is often far removed from Bach’s and includes a number of alterations to phrases that Walther might have considered awkward (e.g. bar 35, Recit de tierce en taille, Gloria IV) and places where a concerted effort to smooth out Grigny’s unique blend of modality and tonality is evident (e.g. bars 71–2, Dialogue, Gloria VI). But there are also a number of unique minor variants in the form of missing ornaments, petites notes and, in some cases, individual voices (e.g. bar 24, Dialogue de flûtes pour l’elévation), and since there is no musical reason for such exclusions it must be that they were absent from Walther’s source. The same must be said of the missing movements in the Kyrie, which Walther would have included had he access to the copy Bach used.

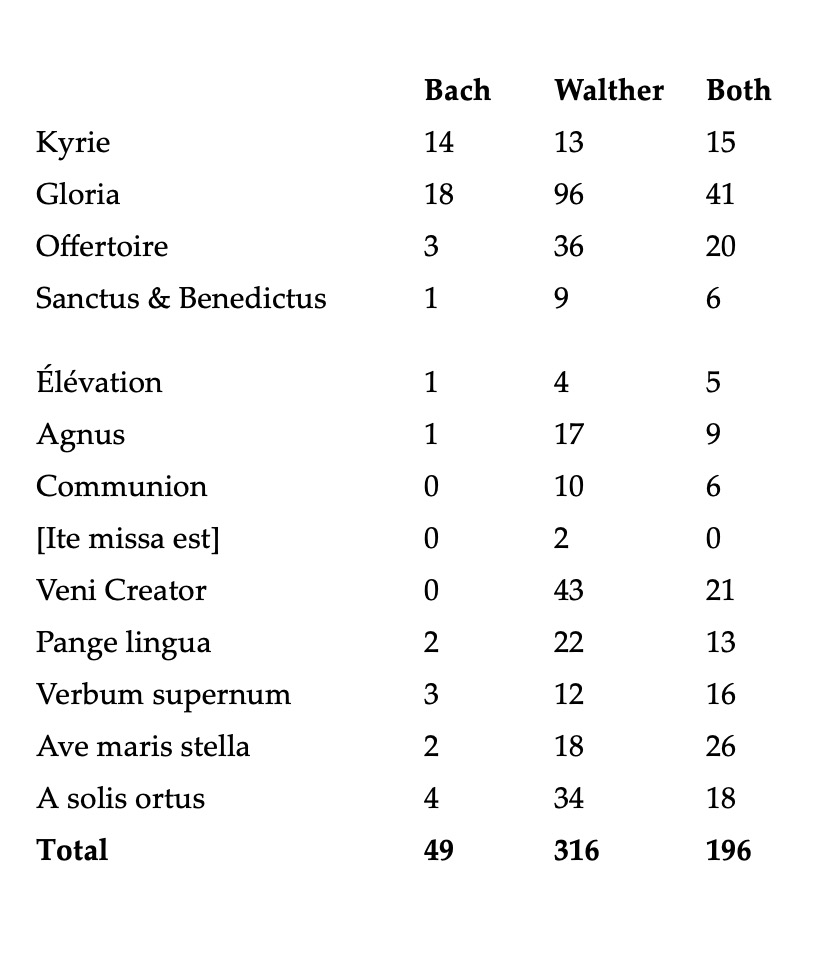

Table 1 provides an overview of the number of unique and common variants in the German sources.

Table 1. Unique and common variants in the copies

of Bach and Walther

Figure 1 . X2 represents a possible parent copy of Bach’s source; Y2 is the proposed parent of the first

Kyrie copied by an anonymous hand into Walther’s source; Z represents the proposed copy from

which Walther’s incomplete first Kyrie derives.

- Dumage, I.er livre d’orgue (1708); Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motets melêz de symphonie (1709); Philippe Courbois, Cantates françoises, à I. et II. voix (third imprint, 1710); Robert de Visée, Pieces de theorbe et de luth, Mises en partition, dessus et baße (1716); Louis Thomas Bourgeois, Cantates françoises ou Musique de Chambre … Livre II (1718).

- Both editions are housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France and have the catalogue numbers Rés VMB-13 and Vm71834, respectively. Ballard’s corrections are few and address only obvious errors, such as the two pedal semibreves in each of bars 8 and 9 in ‘Et in terra pax’. It is apparent that these were engraved at the wrong pitch, which was rectified by Roussel, who added the right notes without first deleting the mistake. Unfortunately, Ballard’s correction was of little benefit since he reinstated the wrong notes partially corrected by Roussel.

- Quarto oblong format allowed eight sides to be printed on a single blanc (sheet of paper). These were folded twice to produce gatherings of four folios, and it was in this unbound ‘en blanc’ state that much music was sold. I am indebted to Laurent Guillo for sharing his research into printing costs.

- BnF Catalogue Général(<https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb15376254r>).

- Michel Brenet [Michelle Bobillier], ‘La librairie musicale en France de 1653 à 1790, d’après les Registres de privilèges’, Sammelbände der Internationalen Musikgesellschaft, 8 (1907), 411.

- Elizabeth Fau Very, La gravure de musique à Paris, des origines à la Révolution (1660–1789) (Thèse de l’Ecole des Chartes, 1978), 168.

- At the time of printing (2019), this would be the equivalent of approximately €800.

- By means of comparison, François Couperin’s annual stipend in 1690 was 400 livres and the priest-organist at the lesser church of Saint-Barthélemy, Pierre Dandrieu received just half that amount. See François Couperin, Pièces d’orgue; Jon Baxendale (Tynset, 2020), i, and Pierre Dandrieu, Noëls, O filii, chansons de Saint-Jacques, Stabat mater, et carillons, ed. Jon Baxendale (Tynset, 2020), i.

- Fau Very, La gravure de musique à Paris, 186.

- These are Boyvin (1700), Marchand, (1700, now lost but probably the source of the posthumous Boivin edition of 1740), Corrette (1 703), Guilain (1706), Dumage (1708) and Clérambault (1710).

- This was a customary practice for Ballard and a number of publications used engravings from earlier impressions (e.g. Louis Marchand’s first book of harpsichord pieces (1699), which were republished by Ballard in 1702 using Roussel’s plates and supplemented at the same time by a second book). See Jon Baxendale, ‘The Genesis of Louis-Nicolas Clérambault’s Premier Livre de Pièces de Claveçin’, Early Music Performer, 44 (2019), 12–15.

- Jean Henry D’Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin; intro. Denis Herlin (Geneva, 2001), xxi.

- Grigny is not mentioned, for example, in Évrard Titon du Tillet’s Le Parnasse françois (Paris, 1732). Though largely inaccurate, it is often the only biographical source concerning the lives of the better-known Parisian artists, poets and musicians.

- For example, the manualiter Trio (A solis hortus [sic]), shares its opening staves with the end of Fugue à 5. The plate contains nine staves: the three-stave fugue takes up the first system and approximately half of the second (staves 1–6); the two-stave trio takes up the remainder (on staves 3–9), its first six bars being engraved as two three-bar systems. Stave 6 begins as the lowest stave of the fugue’s final system and becomes the upper stave of the trio’s second system; stave 7, which is used only for the trio, has been partially smoothed out to ensure it is not visible under the fugue. The relevant page from the 1711 reprint is shown on the cover of this issue.

- For example, a contract dated 22 March 1760 between Jean Baptiste Forqueray details each party’s obligations; Fau Very, La gravure de musique à Paris, 168.

- F-PnVm7-1112: Recüeil de trio nouveaux pour le violon, haubois, flute sur les differents tons et mouvements de la musique avec les propretés qui conviennent a ces instruments et les marques qui peuvent donner l’intelligence de l’esprit de châque pièce. The book is largely overlooked today, possibly because its contents are of a mediocre quality. However, it does contain a very detailed and valuable explanation of ornamentation. According to an inscription in Sébastien de Brossard’s hand on the title page, the book was presented to Brossard by ‘Mr. Toinon maître de pension a Paris pres le college des quatre nations’. Brossard was a composer and collector of music, at first in Strasbourg, where he was a canon and Maître de Musique at the cathedral, before moving to Meaux Cathedral in the 1690s. He is best remembered as the author of Dictionaire de Musique (Paris, 1703).

- See Baxendale, ‘The Genesis of Louis-Nicolas Clérambault’s Premier Livre de Pièces de Claveçin’.

- F-V Ms Mus 61a and b: Pieces D’orgue du Grand Marchand original de l’auteur.

- Tim Blanning, in The Pursuit of Glory: Europe 1648-1815 (London, 2008), 7, indicates traveling distances from Paris to several major cities in France. Using his calculations, we can estimate that a stage coach would be able to cover c 50 kilometres per day.

- D-B Mus Ms 8550 and D-F Mus Hs 1538.

- For example, see Jean Saint-Arroman’s commentary in Nicolas de Grigny, Premier livre de pièces d’orgue; commentary by J. Saint-Arroman, Philippe Lescat, Pierre Hardouin and Jean Christophe Tosi (Fuzeau, 2002), vii.

- This was customary practice among established composers such as Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (1710) and François Couperin (1713). Unfortunately, there is no record of Grigny’s privilège being presented at the Chambre syndicale de la Librairie et Imprimerie de Paris, which would provide us with an idea of its type and duration. This suggests the privilege was issued in Reims, for which records have yet to surface.

- Karin Beisswenger, Johann Sebastian Bachs Notenbibliothek (Kassel, 1992), 198.

- Subsequent repeats of the same note within the bar where an accidental has not been restated.

- Exact figures are: 8.73, 56.33 and 34.94 percent, respectively. If we discount the Kyrie, which is incomplete in Walther’s copy, these figures become 6.74, 58.38 and 34.87 percent of a total of 519 variants.