By Jon Baxendale

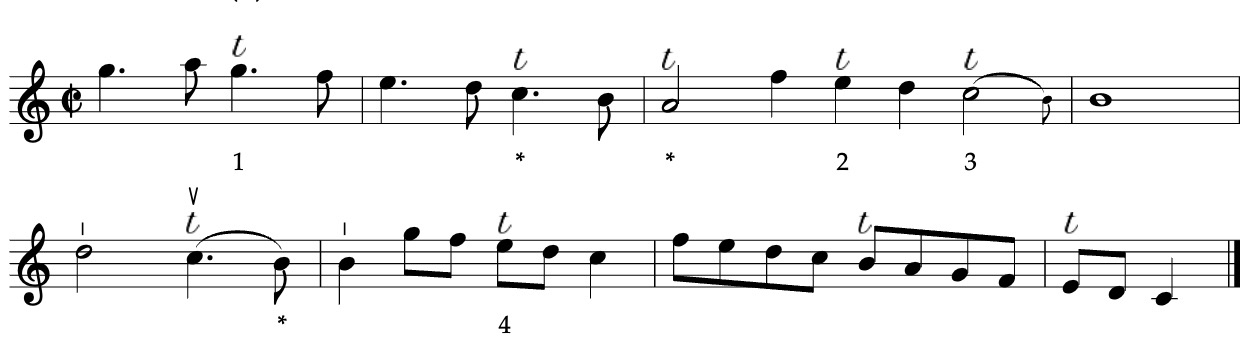

When considering that later grand siècle composers incorporated myriad ornaments into their music, the meagre offerings found in some of the earlier printed books leave performers with the task of adding their own and, in doing so, determining what would be most appropriate. This article, adapted from the first volume of Nicolas Lebègue: Pièces de clavecin et d’orgue, ed. J Baxendale (Tynset, Lyrebird Music, 2024), examines those books published in Paris in the 1680s and discusses the range and nature of ornaments that contemporary performers might add when faced with pages that are nearly devoid of even the most basic agréments.

Nearly all harpsichord and organ books published after 1665 explain the symbols they use, though it is clear from prefaces that their explications were designed to accommodate a growing amateur market rather than professional colleagues. Manuscripts, though, sometimes tell a different story. For example, the second Bauyn manuscript (F-Pn, Rés. Vm7 675 –– a principal source of Louis Couperin’s music) is almost bereft of ornaments. Its accuracy suggests someone with considerable musical knowledge copied it, and while its few ornaments were probably transferred from its source, it is unlikely any were added supplementally. Indeed, if we go by Couperin’s organ music, it is equally unlikely any of these are original.1 Bauyn contrasts considerably with another Couperin source, the Parville manuscript (US-BEM, MS–778), which contains 56 of his pieces, some of which are unicum. The document was hastily compiled, is crude, and has all the hallmarks of amateur work despite its contents being organised into suites (as opposed to Bauyn’s anthological approach, which groups the pieces according to tone and genre). However, it contains egregious errors like the repetition of phrases or whole bars. We know some of these were in the copyist’s source since repetitions are sometimes wrong, suggesting the copy is much further removed from the prototype than Bauyn. We should note, though, that despite these shortcomings, Parville’s ornamentation is generally sensible, which is why it provides most of the ornaments for modern editions of Couperin’s music. We may be confident that Bauyn represents the work of a professional musician: there would be no point for seasoned harpsichordists to write in symbols since they would be well aware of where they should be placed and how they should be played.

The density of ornamentation seen in harpsichord and organ books should be briefly addressed. Lebègue grudgingly gives us just five to work with, four are used with significant frequency.2 When comparing these with the ornaments in D’Anglebert’s Pieces de clavecin (1689), a different picture emerges: its ornaments are rich and complex, and some have several species. It has long been thought that some of these were of the composer’s devising, though the probability is that he added nothing new to the repertory others had at their disposal. For example, his various species of coulement were described by Muffat as subcrepitatios less than a decade later and the remainder are variations on the usual ornaments in either simple or compound forms, and D’Anglebert’s role appears to have been that of a codifier. While he sets himself apart from most others because his music is particularly abundant in ornaments, his is a unique case that requires a little scrutiny.

As far as we know, D’Anglebert’s Pieces is the only keyboard book of the seventeenth century engraved on copper. It is dedicated to his erstwhile student, the Princess of Conti––the legitimised daughter of Louis XIV––and her assumed patronage of D’Anglebert probably extended to financing the book’s production. While more research needs to be done on engravers’ fees, we know from the records of the notary Louis Billeheu that a 1720 contract between the composer Thomas Louis Bourgeois and graveur noble Claude Roussel required a payment of ‘four livres ten sols in coined silver for each perfect page or plate’.3. It has not been possible to trace this particular work, though the price suggests it was engraved on copper. When scrutinising other known Bourgeois publications, we may be confident that it had a relatively simple layout free of heavy stave paraphernalia. Indeed, it would be interesting to discover what fee Roussel would have commanded when faced with the musical complexities of a composer such as D’Anglebert, even in 1689, when commodities in France had yet to endure the hyperinflation of the 1690s. In D’Anglebert’s case, the engraving would have required new punches for most of his ornament symbols––especially those he devised––and a modicum of hand engraving. In these situations, a patron’s support would have been requisite to help produce the ‘planche parfait’. While speculation, such a scenario might explain why D’Anglebert’s ornamentation is so rich and others’ is meagre by comparison. There is no evidence to suggest that others did not richly ornament their pieces when playing. However, there can be few doubts that, given the expenses involved in printing a book, the more impecunious composer might have looked to reduce costs elsewhere. That might well have extended to everything other than the most basic information, ornaments included.4

While D’Anglebert’s music gives us plenty of clues about the range and nature of the agréments players used, it is unfortunate that none thought to discuss them in much detail. Every aspect of seventeenth-century artistic life was governed by le bon goût, which was probably parsed as regularly in coffee houses and salons as it was in literature, and it is likely that ornaments were as equally dissected as other facets of musical taste. Indeed, we begin to understand their importance when reading the preface of François Couperin’s third harpsichord book (Paris, 1722), where he admonishes players not to add or subtract ornaments since, in doing so, the senses of ‘persons of true taste’ might be offended. Therefore, it might seem somewhat incongruous that we must look to a Franco-German composer for detailed –– if not sophistic –– instructions on playing French music. Georg Muffat was a Savoyard by birth but Alsatian by adoption and, for a decade beginning in 1663, studied in Paris, ostensibly under the direction of Lully. His discussion of ornaments in the preface of Florilegium secundum (1698) provides valuable information on where we might place ornaments and how they should be approached. While the Florilegium book is for string players, the pieces are in the French style, and most of Muffat’s suggestions are readily adaptable to any instrument:5

1. Pincements may be placed anywhere except on quick notes, and if the speed is not too fast, they may be placed on successive ones.

2. Pieces or sections, ascending or descending, should not begin with tremblements. An exception is made for mi or #, where a simple tremblement or tremblement et double may be used.6

3. When ascending by step:

A port de voix might be employed on good notes [i.e., strong beats] (1); this might be combined with a port de voix-pincé (2). If note values are quick, the port de voix should be saved for the following longer good note (3).

A port de voix might also be added, as might a slurred tremblement.7

A tremblement combined with a turn might be used on its own (4) or prepared with an anticipatory note (5).

A port de voix might also be added (6), as might a slurred tremblement (7)

Executing a tremblement on good notes in ascending passages sounds harsh. If required, it may be softened with a turn (8).

The exception is that mi and sharps should always be ornamented with a tremblement or pincé, as long as the notes are not too short (9).

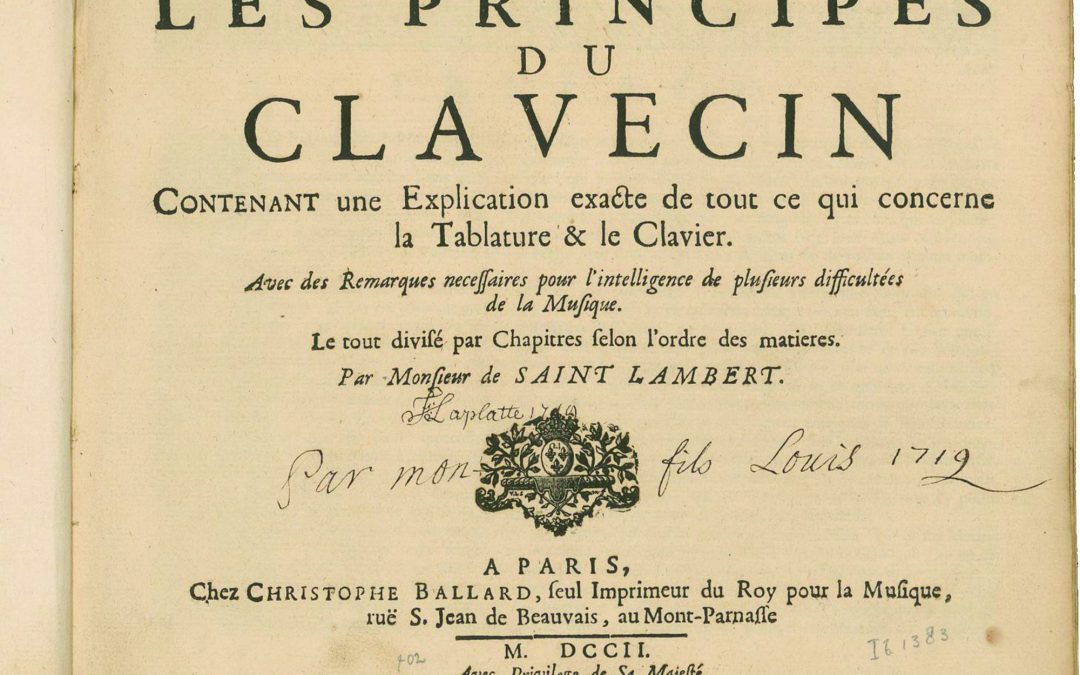

Ex. 01: Muffat, Florilegium secundum, Example Rr.

4. In descending passages of stepwise movement:

Good notes, especially dotted ones, are to be played with light tremblements (1).

Weak descending slow notes also benefit from this approach, whether alone (2) or with an anticipatory remissio (3).8

Rapid descending passages are played with tremblements only on certain good notes.9

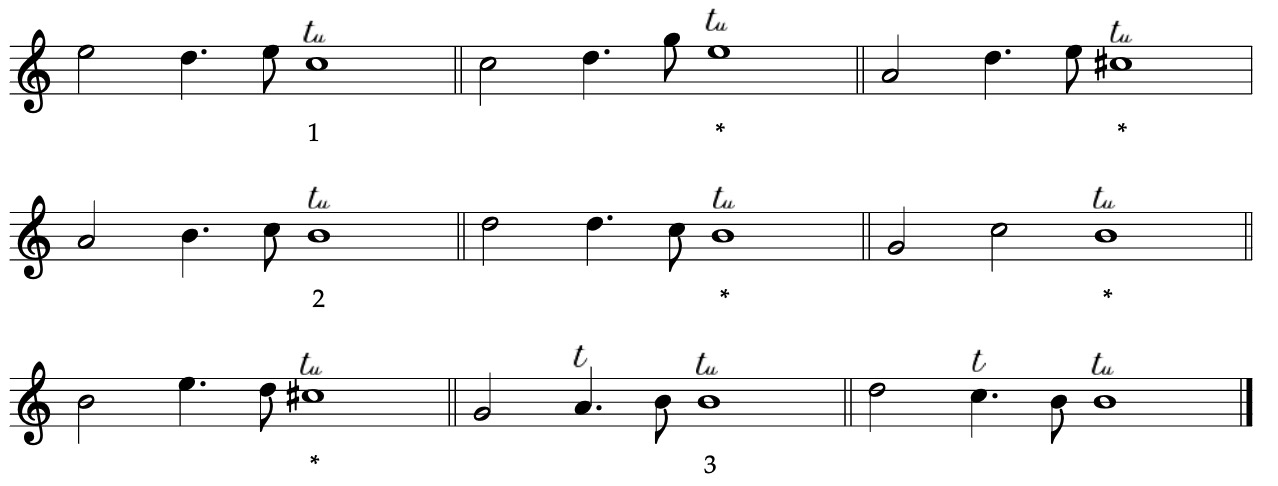

Ex. 02: Florilegium secundum, Example Ss.

5. In ascending leaps:

A port de voix is added to good notes either by itself (1) or with a pincement (2).

Notes might also be played with a confluentia to enliven the harmony (3) or with a combination of a confluentia and tremblement (4).10 Muffat claims this to be the most ‘beautiful’ approach.

The liveliest approach is to use a trait (5) but this should be used only with a degree of discretion.

A leap of a third is best filled with a coulement (6).

It is an error to leap up to a tremblement, although this is permitted if the ornament is placed on mi or a # (7).

Ex. 3: Muffat, Florilegium secundum, Example Tt.

6. In descending disjunct passages:

Tremblements are infrequently used, except on leaps of a third (1), leaps down to a mi or # (2) and should be simple or use a double.

The most agreeable approach is to use a confluentia with a delicate tremblement and coulement on the final note of the descent.

Ex. 04: Muffat, Florilegium secundum, Example Vv.

7. At cadences, tremuli are effective only on specific notes:

Notes that end cadences are seldom given a tremblement unless approached from a third above (1).

Notes that descend by step (2)

Notes that are approached by a port de voix and which are either a mi or # (3).

Ex. 05: Muffat, Florilegium secundum, Example Xx.

While the detailed instructions Muffat provides might be considered the work of an obsessive pedant, they underline the importance of subtle ornamentation and demonstrate how and when it should be applied according to taste. Indeed, parallels between Muffat and D’Anglebert are clear: Muffat provides clues concerning the range and nature of improvised ornamentation that D’Anglebert was fortunate enough to be able to engrave, but a case has been made where some composers sacrificed saturating their music with the correct density of symbols because of cost. Those provided would suffice for the market Lebègue et al. fostered during the last quarter of the seventeenth century, and for those with le bon goût and knowledge of the type of advice Muffat proffers, ornament symbols and petites noteswould have been regarded as unnecessary.

• • • •

Bibliography

Jean-Henri D’Anglebert, Pieces de clavecin (Paris, 1689).

Jon Baxendale, ‘Publishing organ music in grand siècle France’, The Journal of the Royal College of Organists, 17 (forthcoming, 2025).

Louis Couperin (ed. G Oldham), Pièces d’orgue (Monaco, Éditions de l’Oiseau-Lyre, 2003).

Henri Falk, Les Privilèges de librairie sous l’Ancien Régime. Étude historique du conflit des droits sur l’œuvre littéraire (Paris, A. Rousseau, 1906).

Elizabeth Fau Verry, La gravure de musique à Paris, des origines à la Révolution (1660-1789), PhD dissertation, Ecole des Chartes, 1978.

Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre, Les Piéßes de Clavecin (Paris, 1687).

_____, Pièces de clavecin, ed. J Baxendale (Tynset, Lyrebird Music, 2025.

Georg Muffat, Florilegium Secundum für Steichinstrumente (Passau, 1698)

_____, Apparatus musico-organisticus ed. J Baxendale (Tynset, Lyrebird Music, 2020).

- Of the 70 Louis Couperin fantasias and versets in the Oldham manuscript, not one contains an ornament (cf. Couperin, ed., Oldham, 2003). Because of this, it could be that the Bauyn manuscript’s source was an intermediary copy and not Couperin’s prototype.

- In the first dances of Lebègue’s Suite I in Livre second (excluding the prelude and major-mode pieces), we find 342 ornaments in 133 bars. Compared with the same movements in D’Anglebert’s first suite, which contains 495 ornaments in 164 bars, D’Anglebert uses 17% more ornaments per bar. Lebègue restricts his ornaments to those depicted in his ornament table, while D’Anglebert uses six frequently and nine classed here as others (double double cheute a une notte seul). The result is significantly different when looking at all the ornaments in each publication (excluding D’Anglebert’s preludes). Including petite-note agréments, D’Anglebert contains 1,433 ornaments in 643 bars, giving a relative density of 2.22 per bar. Lebègue uses 1,980 in 1,252 bars, which results in a density of 1.58. Adding Jacquet de la Guerre (1687) to the equation, whose relative density is 1.71, reveals that D’Anglebert uses 32.8% more ornaments than Lebègue and 25.1% more than Jacquet. Lebègue and Jacquet’s books were chosen because of their similar date to D’Anglebert’s publication.

- F-Pan, MC/ET/LIII, 207, 6 October 1720, Doc. no. 12, cited in Fau Very (1978, 91): ‘[…] quatre livres dix sols en argent monnoyé pour chaque page ou planche parfaite´.

- Among these costs was the acquisition of a privilège du roi. It ostensibly provided authors with a form of copyright in France, though it was also an easy means of securing income for the state. Failing to obtain one carried strict penalties, which included ‘the whip, prison, banishment, [or] death’ (Falk, 1906, 41). However, punishments were often not as draconian and usually resulted in confiscating and destroying the printed material. Two copies of any published book were required to be delivered to the King’s library, with a further nine to be sent to the Chambre syndicale; failure to do so would result in a fine of 300 livres.

In 1663, the cost of obtaining a simple privilege was free, though one was granted only in exchange for a payment for certain rights. A regulation of 2 October 1701 brought in a permission simple, which did not require a certificate of ownership and cost five livres. It is uncertain what Lebègue would have been charged for a ten-year privilège générale in 1675, though we do know that, by the 1750s, an octavo or quarto imprint cost 60 and 120 livres, respectively, for up to 1,500 copies.

Laurent Guillo’s research into the Ballard workshop has revealed that excluding the cost of paper –– which had to be thick enough to withstand the press –– two formes (printed sheets) of engraved music cost approximately twelve sols for large print runs to 29 for shorter ones. Considering that Lebègue’s stipend at Saint-Merri was just 400 livres per year, it is easy to see why such ventures constituted a considerable investment (cf. Baxendale, 2025). - Muffat produced four simultaneous editions of Florilegium secundum in German, French, Italian and Latin, each of which has a different slant, according to the intended audience. The Lyrebird Music edition of Muffat’s Apparatus musico-organisticus (2020) has translated his comments and these are discussed in detail. The translation here is primarily based on the German version, though there are no noteworthy differences in the other versions. Where possible, the Latin names Muffat gives ornaments has been altered to French. Instructions irrelevant to keyboard music have been omitted.

- By mi or #, Muffat means the third degree of any of hexatonic scale. This was always a semitone from the fourth note and would be applied to E, B or A (if there is a Bb). Such placing seems common to most European music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries so we should assume this to be convention. Tremuli seem also, by convention, to have been executed on any chromatically altered note.

- By ‘slurred tremblement’, Muffat means an anticipatory note: if the tremblement is on d, its anticipatory note would be the same. The example Muffat provides has the rhythm of a crotchet and quaver combination.

- A similar petite-note anticipation of the note that follows (cf. previous footnote).

- Muffat is somewhat vague concerning what is meant by ‘certain good notes’ (4).

- In keyboard terms, a confluentia would be approaching a note from a third above (as in a tierce coulée) and executing a tremblement lié on the parent note.