By Jon Baxendale

These notes are adapted from the Lyrebird Music edition: Louis Couperin: Pièces de clavecin ed. J Baxendale (Tynset, 2022).

Unless players ignore the subtle implications of the various lines, note-grouping and written-out ornamentation in Louis Couperin’s preludes, they should find few problems building successful interpretations. No single approach is correct, though it is helpful to understand some pitfalls one might encounter. The issue is that while later authors addressed various musical topics to cater to a growing amateur music-making public, none before François Couperin (2/1717) explained aspects of their performance:

Although these Preludes are written in measured time, there is, nevertheless, a tasteful custom that should be followed. I will explain. A Prelude is a composition in which the fancy can free itself from all that is written in the book. However, it is all too rare to find prodigies capable of producing them spontaneously. For those who resort to non-improvised preludes, it is necessary that they be played freely, without attaching too much precision to the movement–at least where I have not expressly written the word mesuré: Thus, one may dare to say that, in many aspects, music (compared to poetry) has its prose and its verse.

One of the reasons I have measured the preludes is that they will be easier when teaching or learning them1.

Couperin suggests that his preludes should sound as if they are improvisatisations, and his comparison of verse and prose is especially revealing when related to Louis Couperin’s music. We can view the dances as similar to verse, characterised by the balanced and structured formalities expected in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French poetry.

Prose, on the other hand, is irregular; its rhythms are flexible, and it is subject to a constant shifting of pace, phraseology, and rhetorical content. Louis Couperin’s choice of notation emphasises this critical aspect of performance and its oblique appearance in the Bauyn manuscript ( F-Pn, Rés. Vm7 674), while possibly a peculiarity of its scribe’s style, nevertheless suggests the fluidity that is at the heart of the music.

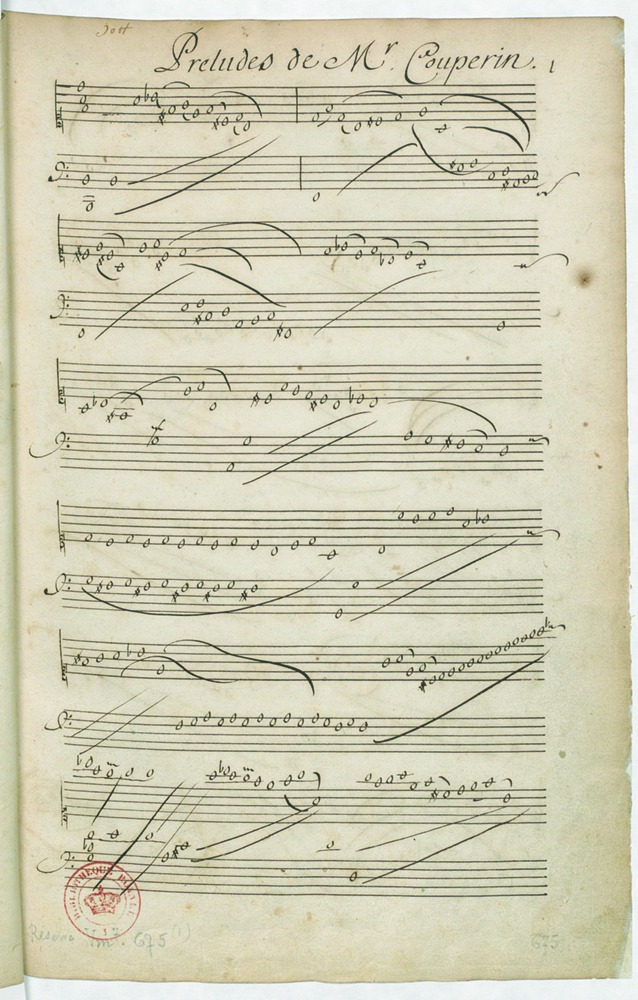

Fig. 01: The first page of Couperin’s preludes in the Bauyn Manuscript

demonstrating the left-leaning style of his calligraphy.

Understanding a prelude’s metrical framework is critical for its performance. While it is essential to maintain a sense of rhythmic freedom, defining the grouping of figurae over lute-like diapason notes is often straightforward. The opening two lines of Prelude 1 serve as a good example:

Ex.01: Prelude 1: opening demonstrating the harmonic movement of the bass.

Here we see a cogent progression marked in red, which provides structural clues for the player. Each ‘diapason’ occurs between these metrical points. This type of bass is not restricted to toccata-preludes, as demonstrated in the opening lines of Prelude 2:

Ex. 02: Prelude 2, opening.

Again, we see a similarly organised bass (in red): L1–2 and R1 outline the tonic chord, while R2–4 (in blue) behave as an allemande-like suspirans.

Understanding the bass is important for delineating harmonic movement, although it becomes easier when we grasp the roles of the various lines present in the music. The least common are vertical lines, which appear in three forms: to mark the beginning of a new phrase or harmonic group (e.g., Example 01), to indicate ensemble notes between the upper and lower staves (e.g., Prelude 10, line 4), or to accurately place notes when another part is engaged in fluid passagework (e.g., line 5 of the same piece).

Regarding the curved lines, the issue does not lie in their meaning, as most are self-explanatory, but in their placement, which can sometimes be ambiguous. Scrutinising note grouping helps clarify some of these ambiguities. For instance, in the opening of Prelude 1 (Ex. 01, above), the sustained bass octave is easy to interpret: its notes are held for the duration of the right hand’s figuration before progressing to A. Meanwhile, two types of lines appear in the right hand. While those on b-flat’ and f’ suggest that the notes are held, they also indicate the hand position to be adopted. Therefore, the little finger might be used on the first note of each group, allowing the remaining figuration to fall comfortably under the hand. Similar occurrences can be found elsewhere (e.g., at the beginning of preludes 2 and 6). Returning to Prelude 1, the initial flurry of activity in the upper stave includes two sets of paired notes. The diminished fourth formed by notes 2 and 3 and 6 and 7 exemplifies an interval of which Couperin is exceptionally fond. While the lines emphasise these ‘surprise’ moments, they may also indicate a liaison whereby g’ is sustained while e’ is struck, and so forth.2 Harmonically, Couperin establishes a typical rhetorical gambit by immediately progressing to a 6/4/2 chord. However, instead of returning to the tonic, he heightens the drama by transitioning to a diminished chord of B. His gateway to each chord is marked by a diminished fourth, and the lines draw attention to this while outlining the harmonic movement.

We see from the following how this is organised for the first line:

Although lines help establish significant intervals and harmonies while providing a metrical framework upon which figuration may be hung, others serve a different purpose. In the following, the lines are used to suggest a highly declamatory moment where F# appears to receive special treatment, as three lines converge upon it. Whether or not the first and second of these cross-stave lines originate from g’ and a’ or from a’ and b’–with different editors offering alternative solutions–the harmonic movement favours the approach taken here. However, it is possible that the lines serve no other purpose than to highlight the leap of a diminished fifth and, in this instance, might be considered rhetorically as a figure of interruption.

Ex. 05: Prelude 13, line 1.

While we observe from Couperin’s contemporaries that the port de voix is a standard device, it is important to remember that it is seldom employed in the dances and is more commonly found in the allemande-type movements of the preludes. With this in mind, it is possible that the port de voix served a more expressive role than other ornaments, which is undoubtedly true in the rhetoric-laden opening of the prelude. A suspirans leads to the tonic chord and is followed by a more urgent repetition that culminates in a languid port de voix. This prelude is one of two that make extensive rhetorical use of the ornament, with no fewer than seven occurrences.3

Another critical aspect is the interpretation of the opening chords of the toccata-preludes. A clear link between Froberger and Couperin is demonstrated in Prelude 6 since not only does the other source of Louis Couperin’s music, the Parville Manuscript (US-BEM, Ms 778), append ‘a limitation [sic] de Mr. Froberger’ to its title, but Couperin quotes the first three bars of Froberger’s Toccata I from his 1649 collection:

Ex. 06: Froberger: Toccata I, bars 1–2; Couperin: Prelude 6.

Froberger’s toccata begins with an undecorated A minor chord. While we may conjecture that he played such chords in a style closely resembling that of his teacher, Girolamo Frescobaldi, Couperin writes out a decorated arpeggio, presumably mimicking Froberger’s playing. Arpeggiating opening was first mentioned in the preface of Frescobaldi’s Toccate e partite d’intavolatura, libro primo (Rome, 1615), where he informs his readers, ‘The beginnings of the toccatas should be played adagio and arpeggiated’.4 Couperin’s interpretation fulfils the second part of Frescobaldi’s requirement. Although the prelude seems to call for a display of virtuoso playing, an adagio approach would be equally valid, if not preferable. Whether such an opening should be applied to the first prelude, which begins with a straightforward chord on the tonic, cannot be said with certainty. Figuration and harmonic progressions reminiscent of Froberger are distinct features of Couperin’s preludes. However, since he is particular about notating these pieces in a specific manner by leaving all but the rhythmic element to chance, it seems reasonable to assume that a straightforward chord is all he requires.

While Couperin was the first to use void notation for his preludes, it is important to consider those of other composers when determining the type of rhythmic figuration that could be adopted. D’Anglebert certainly recognised the limitations of this notation, as he took steps to convert three similarly notated preludes in his autograph collection (F-Pn, Rés 89ter) for publication in 1689. Before D’Anglebert, Lebègue (1677) used standard rhythmic notation and employed lines to demarcate harmonic movement. Then came Elizabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1687) and others, all of whom added rhythmic notation to varying extents. Only Gaspard Le Roux chose to follow Couperin’s example, though this sufficed for his purposes. David Chung makes several observations regarding the process D’Anglebert employed when converting his preludes, although the most relevant to Couperin concerns the outlining and modification of ornaments. Chung suggests that Couperin might have taken a similar approach had he wished to publish his preludes, which Chung demonstrates by transcribing Prelude 7 using similar techniques, and a modified version is provided below in preference to a complete rhythmic transcription, which would serve little purpose and might be taken too literally by inexperienced players.

Ex. 07: Couperin, Prelude 7, partial transcription by David Chung after D’Anglebert (modified).

Notably, Chung’s interpretation highlights most of the prelude’s perceived rhythmic figuration and ports de voix, although its harmonic progressions are left undisturbed.

Melismas and traits are generally self-explanatory and may be performed according to the surrounding figuration. Fast, sweeping runs can significantly enhance the rhetoric of a passage, especially if they lead to a declamatory moment. In other cases, scalic passages seem to dissipate any apparent turbulence from the preceding figuration. For example, consider the beginning of line 8 of Prelude 13.

Ex. 08: Couperin, Prelude 13, line 8.

It is the second of two traits and, as a figure of repetition, is ripe for rhetorical exploitation. Landing on the following 6/5 chord of D major softens the declamation of the previous passage, which is best approached by slowing the pace at the beginning of the line. This allows the player to pause briefly before embarking on what becomes a more turbulent journey, filled with repeated diminished fourths, that propels the music towards its next cadence.

It is important to maintain a melodic thread, even if the melody seems visually broken. In line 10 of the same prelude, we observe this occurrence where, before the minor seventh on C (lh, note 4), there is a double-touch preparation for a port de voix in the right hand.

Ex. 09: Couperin, Prelude 13, line 10.

Once again, we encounter a moment for reflection, marked this time by a vertical line in the upper staff, before proceeding with more melismatic runs. In this instance, it would be incorrect to let the left-hand dyad sound before completing the ornament. Similar moments often arise in the preludes, and players should aim for both harmonic and melodic cohesion when planning their interpretation.

- François Couperin (2/1717) ‘Quoy que ces Préludes soient écrits mesurés, il y a cependant un goût d’usage qu’il faut Suivre, Je m’explique. Prélude, est une composition libre, ou l’imagination se livre a tout ce qui se prèsente à elle. Mais, comme il est assés rare de trouver des genies capables de produire dans l’instant; ilfaut que ceux qui auront recours à ces Préludes-réglés, les joiient d’une maniere aisée sans trop s’attacher a la précision des mouvemens; a moins que je ne l’aye marqué exprés par le mot de, Mesuré: Ainsi, on peuthazarder de dire, que dans beaucoup de choses, la Musique (par comparaison à la Poésie) a sa prose, et ses vers. | Une des raisons pour laquelle j’ai mesuré ces Pre ludes, ca, eté la facilité qu’on trouvera, soit à les enseigner; ou a les apprendre’.

- Such rhetorical flurries might be further highlighted by using Lombardy rhythms of varying proportions (e.g., semiquaver–dotted quaver), a device favoured by several grand siècle composers who would ‘slur’ pairs of notes. However, it would be wise not to adopt too formulaic an approach for fear of an interpretation lacking a sense of spontaneity.

- The other is the short Prelude 7.

- ‘Li cominciamenti delle toccate siano fatte adagio, et arpeggiando’.